I still have lots to say about how I dealt with dyslexia. Please, bear with me.

It has been a long, lonely crusade, the one aimed at familiarizing myself with the process of learning. Had to understand it, its components, how the parts fit in the process, their sequence, their relative importance, the steps that could be skipped, the others fundamental. I had to decorticate to the smallest elements the advent of learning, how it manifested itself and how it could be verified.

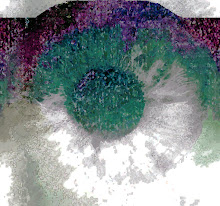

Up to the moment I was told about the condition, I thought among other things that I had an eye problem. Of course I had realized as a child that what I saw on a page didn’t correspond to reality. I knew that from feedback. I knew, in other instances, that I was much slower than other kids. I also knew the results of what I did often failed to match expectations.

When I was in grade one my father had spent a few minutes at the dining room table – the only time he ever looked at my homework – to question me about what I was studying. He had gotten so mad, insulting me, throwing the sheet of paper away with disdain. He had said I was stupid.

I was taken aback. It was the first time I was hearing that word to describe who I was. I considered the word from all its angles, trying to figure out what my father had meant. I was puzzled. Not so much by the possibility of being stupid, but by the fact that the sheet of paper had directly led to the conclusion. I was looking at it in a deep effort to understand the link between my father’s verdict and the paper’s content. I felt it was essential for me to find that answer.

And I can say that everything after that incident has always revolved around the effort to find an adequate explanation: How does the relationship between what I do and stupidity manifests itself? How can I intervene to change it? How can I disrupt or alter this connection? That is where my answers were, I thought.

With time – we’re talking here of decades, not months or years – I realized there were two major kinds of pitfalls I had to watch for.

One, the most obvious mainly to others, had indeed to do with my eye. I don’t see things the way I should. This leads to writing a sentence, for example, and seeing only my intention, not what I actually wrote. The use of the wrong letters, the frequent repetition of the same words, the absence of key ones or of some syllables, the inversion of letters to form syllables, or writing the wrong letters, confusion between nouns and adjectives, the wrong spacing between words, syllables or letters, the arbitrary use of upper and lower cases even within words themselves, all of this had led me to believe my eyes could never be trusted. That was not such a bad statement to start my exploration of the problem.

Probably in those days, the late fifties and early sixties, dyslexia was much less known than it is today. Teachers, at least those I had, weren’t on the look out for the symptoms. Or perhaps these weren’t identified as precisely as they now are.

These difficulties that were mine, I later learned, are categorized as graphic problems typical of a specific type of dyslexia. They’re not hopeless. With intense care, constant self-discipline, they can be repaired. Not completely, but sufficiently. So instinctively, with much concentration, that’s the path I undertook to follow. Always trials and errors. Using my fingers to block out words, isolate some, going very slowly, checking seven times. By the way, that was my magic number when I was a child. I don’t know why I picked it. It seemed a big number. I had to check everything seven times. It was an obligation I had imposed on myself. Verifying the universe seven times. It sounded safe.

The second type of dyslexia I seemed to suffer from is of a more complex nature. It has to do with meaning. Even today, I find it difficult to describe the characteristics of this major flaw. It’s more ethereal. This deeper kind of problem goes beyond the challenge of reading and writing. In this case, speech and thinking are also affected.

The superficial type of dyslexia, if I can call it that, the one impairing written language, I understand it as the result of wrong connections in the mind, but because there are connections, they can be rerouted.

The deeper type of dyslexia is one of no-connections. There’s nothing to work with. It just ain’t there.

The meaning’s gone.

I guess this is how my “house of thoughts” as a kid came to be. Miraculously, I had found a dimension in my mind where meanings could exult. But I couldn’t export these meanings into the real world. But I knew meanings were there, in a leak-proof environment shut tight on itself, uncommunicative with the outside world. But it was there. As time went by, I became aware I was getting better and better at accessing this bubble. I simply hadn’t found a way to translate its content in a way that would have been acceptable to others and conducive to proper actions.

To be honest, I never came up with a satisfying solution. I developed instead a wide range of compromises, never a definitive fix. Little things. Pieces of recipes. Scraps of ideas to implement. A tiny something here, a bit there, a crumb of solution over there, a drop of this or of that. All combined, I could reassemble a passable meaning. Always partial, with holes, never as grand and beautiful as it should have been.

That has always made me sad. Believe me. Very sad. In some strange fashion, I can emotionally compare what I have written with how it should have been written even though I can’t reproduce that, and feel the inadequacies. How poor it is, effect-wise, from a reading perspective.

I now think that the crises of physical paralysis that plagued my childhood were, possibly, a sort of parody of what was happening in my mind. Was I unconsciously mimicking with my body how I felt inside my head? A prisoner. Unable to get out. Caught. My thoughts buried alive. Unheard. An urge to shout without a sound, a word willing to lend its support. Forever locked in a dark cave. All marvels untouchable.

I knew so well this was who I was. I knew it, and in more than one ways this was the worst of it. The fact that I knew.

I can thank anger though. Seems quite awful, I understand, to view violence, rage, hyper-negativity as being beneficial tools, but I see no others with the strength and the kind of lasting ramifications capable of effectively face in-depth distorted traits like mine.

It is the power of my anger, my daily anger, the anger I was feeling every minute of my life, which carried me. I was given only one intact ability, a single faculty as a weapon-tool: the one to be totally angry. I had to use it. I had nothing else that was concrete enough to last throughout the years I was going to need if I wanted to function. My anger, and only my anger allowed this.

Yes, my anger was going to persist. My anger had endurance. It was able to renew itself every morning, without signs of weakness. Whenever I would falter, anger wouldn’t. If I became tired, anger would force me to stay awake. It would keep me up and standing. It would push me forward if I ever became tempted by retreat. It would never let go of me. My only trustworthy ally. If I ever gave up, anger would hurt me, and hurt me, and hurt me until I completely surrendered to its influence, picking up my bruises and despair to continue the march. That’s what anger was going to do for me. And in exchange, I would be nourishing it. That was the deal, I might say.

In other words, I’m telling you that I am, as a person, an ode to anger.

I represent one of its achievements. I’m its product. The result of its vigor and character. Its unceasing stamina.

I would not be your mother or grand-mother if it wasn’t for that icy-cold unrefined anger. You would not exist if it hadn’t been there, years ago, to torture me. And then to compel me. I would not be there to tell you the story if it wasn’t for the persistence and stubbornness of sublime anger. That rage, it was everything to me. Bad and good. What I could acquire through it, and what it would cost me to use it. It’s all there in one package, the person I became.

One meaning I had no problem with, as you can see: Crude anger.

My statement here is quite indicative. It’s not a light statement. It contains the very essence of my biggest difficulties at the time. I could relate in those days to the meaning of the word anger, but I couldn’t lace a pair of shoes. I had no sense of direction either. I was clumsy at arithmetic, confusing the digits 3 and 8, 4 and 5, 6 and 9. Unable to add, subtract, multiply with a pencil, but good at mental arithmetic as long as it’s the noble, uncontaminated idea of three I’m dealing with, not three chairs, not three glasses of water. That is extremely hard to count for a person like me.

Even today when, before a class I must count the number of students present for our records, I can’t. Luckily professors have assistants in our school, and she does the count at my request. If she says there are 27 students in the classroom, I understand what 27 represents, but if I tried to count them myself, I would utterly get confused and mix the digits. I can say 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 in my head. But I cannot count real objects. Suddenly, I forget the order of the words signifying the digits. It becomes a real mess. My heartbeat goes wild. I sweat and panic. So, I use my fingers all the time for small quantities. And for larger ones, well… I’ll pretend it’s a waste of time or that I forgot to do the job.

Same goes for the alphabet. I would not even be able to tell you how many letters there are. I’ve learned it a million times. The info never stuck to me. I call these Teflon-data. They simply glide out of my brain as if they had never entered. I can now recite the alphabet correctly about once out of three or four trials. I almost always trip somewhere towards the end of the series of letters. Never at the beginning. But I know all my letters. I use them all the time. I just can’t remember their order that well. But that’s not so important anyway.

Want something even more ridiculous? At almost 56, if I need to tell a taxi driver to turn right or left, I must mentally ask myself which of my hands is the one used to hold a fork. That’s the right hand. The side not used for the fork, that’s the left one. But if I’m tired or preoccupied by something, I’ll say right when I mean left even if I use the trick. Shit. Do you know how much money and time I’ve wasted this way? I could hit myself whenever I realize, a fraction of a second too late, that the car’s heading in the wrong direction. But when I get it correctly, like a child I feel I’ve discovered an amazing thing. Every time. Beaming with pride.

I remember one afternoon when I was about six, I was late for the school bus that drove me back home everyday. It had left without me. My home was nearby. Only two streets away. Even though one can assume that I had done that itinerary many times by bus, I became petrified. I couldn’t get back home. I somehow know that I knew which way to go, but it wasn’t articulating itself. It wasn’t becoming an action. I couldn’t do it. There was a wall between the steps my legs could perform, and my knowledge of where I lived. I couldn’t send the information to my body and make it walk in any direction. I was lost. There was emptiness in the decision-making part of my mind. The needed data wasn’t arriving.

Understand what I’m saying. The information existed. But it was unmovable. It was refusing to circulate where it would have been useful to make a decision. I had a picture of my house in my mind. I knew what the street looked like. But the images didn’t not correspond to anything I could use to move. They were just floating in my mind, not linked to any practical process. I even had the name of my street in a corner of my head, but it was not plugged to anything workable in terms of solution. Least of all to the image of my street. You see, bits of information, it’s all there, but not linked. Not responding to each other.

I couldn’t either perform the steps to zip a coat. Instructions presented to me, which could be matched to something visible, that could be pictured for instance, were inoperative. But I was able to understand and phrase correctly abstract elements. Words that did not have an image attached to them. I was able to understand existential issues, philosophical concepts, mathematical ideas, because they did not require a physical representation as such. They had, so to give them an existence, an emotional or intellectual pattern I could easily recognize. Something abstract exists as a pure idea and that idea has a buzz to it that I can use to pinpoint it, differentiate it from another one. It’s an essence. It has an almost sentimental texture that defines it. I don’t need to picture it. It doesn’t have a body, a shape, a contour. You do not count an idea. It’s there as it is. I could live with that. I could understand. But if you showed me a book with pictures asking me to retrieve quickly the word for the object that’s depicted, most of the time I fucked up. My mind would go blank.

If you tried to teach me a series of steps to do something concrete, to act on substances, like an experiment in a lab, I became confused. I was unable to follow instructions that concerned tangible objects. There are things in the lab. Each of them unfortunately has a name I can’t access on the spot and all are accompanied by rules for their usage. So if I need to move these objects in a particular order, my mind becomes a mess. But the same experiment, at a strictly mental level, combining atoms into molecules from the point of view of their ideas, was an extremely easy task for me. I never made a mistake, as long as I kept the nomenclature abstract, in the realm of pure thoughts. Careful to never attach to it any form of visual representation. If I try to form an image of the molecule I’m juggling with in my mind, I’m as good as dead. My mental switch gets turned off. There’s nothing I can do.

Images are one thing. Words are another. Concepts go with words; images also go with words. But the three of them together, that’s a no-no. As long as I respect that, I’m fairly ok. But I didn’t figure that out in a day, let me tell you.

I can bring to the surface of my mind rather quickly a conceptual item, but I still struggle, even today, with simple stuff. I look at the banana in the fruit bowl on my table and I can feel the tension the exercise at recollecting its name requires. It’s just a little tension now. Not much, because of habits, of time. But I can still feel it crossing my mind, a slight pressure reminding me of the possibility, even if minimal, that I might screw up.

So, I used to get mixed up with words, writing the wrong ones for example. Or not knowing anymore after having said or written one what it meant. But if I kept it enclosed in my mind, it would do fine. Staring at something that I know I know, on the tip of my tongue it is, nothing coming. Even looking at something familiar, the syllables composing its name becoming unintelligible. Disconnected from the word itself. Just sounds with no meaning. And often not even the right sounds at that.

It is so scary, baby. So tragic. A profound fear. Because all that is known can thus be said to be absolutely unreliable. Terror when realizing nothing from your senses can be relied upon. Because the data, what you see, or don’t see, what you feel, understand, cannot be checked against reality. Even though it’s there, reality being in front of you, you don’t know what to do with it. You can’t sort it out. It’s there, but it’s the same as if it was absent.

One method I developed to compensate for my deficiencies was to fill the blanks with eclectic thoughts instead of fighting to try to get the word right.

If I can’t instantly put a word that I am sure of on an object, I’ll do literature around it. My guessing is quite good actually. I’ll embroider. I’m going to take these abstract notions I find easy to manipulate and pour them into the vacant spaces where something concrete and simple should have been. I can do that really fast. You’ll find me a bit weird true, or overly talkative, a fantasist maybe, a person with a colorful way of expressing herself, hard to follow perhaps, but you’ll get the general meaning (or not, it depends). But I don’t think you’ll conclude I’m sick. I’ll make sure that, together, we go around that peril. I’ll patch. I’ll take you high up in a swirl. I don’t think you’ll guess what I’m doing. You will not see, and that’s my priority, that an instant ago I was confronted with terrible huge blanks, and could not communicate something plain and concrete. So I take my sentences for the ride of their life. Up we go. Passing the time full blast until I’m sure you’ve lost track of what we’re supposed to be talking about. Because I for one do not know. So you’re coming with me.

It’s funny, really. Think of it as a good joke. No malice intended (or hardly none…).

I’m a good teacher. I want you to know that. I’m extremely careful, also patient with my students. I know more about how learning occurs than anyone I’ve ever met. I can identify obstacles and understand how these can be overcome. I not only teach my students the material to cover, but I also try to teach them how to learn it.

I guess you’re wondering how I manage my notes.

With colors. I use color pens and highlighters to make sure the words on the pages I use as a course plan stand out. I also use a panoply of different signs, codes, such as underlining, double underlining, circles around words, squares, or symbols like “x”, dots, slashes, dashes in different colors to separate various notions, words, groups of words. I write notes using different sizes of letters for different words so that they don’t overlap in my mind. To distinguish is the goal. My pages to anyone else but me look like incomprehensible drafts filled with scribbles and marks. But to me, it’s limpidity. It’s happiness, my dear.

And my notes are always as exhaustive as they can be. I can never take for granted that the simplest, most usual, casual word will appear in my mind all by itself, and exactly when it’s needed. It might, but it might not. Planning for the worst-case scenario, that’s me.

Any free time? For hours I recopy words, columns of words, hundreds of them. Practice. Practice. Copying attentively nouns, then verbs, then adjectives from a novel, any novel. Neat vertical rows of words, copied by hand, not on the computer, to strengthen the connection between gestures and lexical intention. For immediate proximity to the page. Endless practice. Everyday. Timelessness taking over. Tracing words, the mind empty, a bit zen I guess, focused on the movements of the hand, the trajectory of the pen, the lines drawn on the paper. An alphabetical yoga.

Oh, another thing, I make more mistakes, or mistakes with larger consequences, in my mother tongue than I do in English, I think. Perhaps because perfecting the language came consciously and at a more mature age, integrating as I worked at improving it the protection mechanisms I needed to safeguard the information. They’re part of the memorized sounds and words. They’re a parallel level activated as I speak or write, at least from the “meaning” perspective. I still do graphic mistakes, but much less about significance. Strange though.

Finaly, I'm an expert at a priori assumptions. To deduct. To infer. To postulate. That is so, so, so much better and safer than to observe... I hope somebody sees how hilarious this is for someone who invested so much in a scientific approach to problems, in the control of all imaginable variables, who believes something is sound only once it can be reproduced in an identical way with the same results. Preferably seven consecutive times before I think it's ok.

Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)