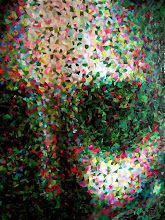

Fingerprints started to be officially used as a way of identifying people exactly 150 years ago today. I have often meditated on what people have in common and what is unique to each of them.

Towards the end of the 50s, my mother had already started her long quest that would lead decades later to her deep involvement in alternative medicines, new age practices, cults, and concerns over invasions by extraterrestrials.

The beginning of that long journey was with vegetarianism, and it often translated itself by the insertion of yogurt into the lunchbox I brought to school. Yogurt, in those days, wasn’t sold in supermarkets. No one in the suburb where we lived had ever heard about it.

I’m in primary school and in the large cafeteria where we all eat, I must put the warm liquefied yogurt on the table that I share with the other children from my group.

Rotten milk, vomit were among the names that flew around me as I tried to eat. The children would even cross the entire room to come and see how disgusting my lunch was, calling more classmates over to make sure I would really feel uncomfortable. And hate my mother even more for doing this to me.

That’s the moment when I knew I had a selfhood, a oneness that distinguished me completely from others.

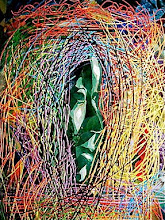

After lunch, we all went outside to play in the schoolyard. The kids had skipping ropes and they would do elaborate tricks, jumping as two long colored ropes drew circles in the air without ever touching.

I had never seen a skipping rope before attending school. It was a sort of magical game that everyone knew about, except me. Again, it confirmed my sense of uniqueness.

I didn’t know where they had learned these tricks. Where was I when it had happened? When the instructions on how to jump had been given - the rope under the feet, then over the head, turning so fast?

I remember, little one. I was sick, at Ste-Justine’s Hospital for children. In a room with another girl, Helene.

Helene, who had suffered from polio at a young age, had her entire body in a long silver cylinder, an artificial lung. Only her head could be seen, her hair and face sticking out, turned towards me as we made conversation.

She was much older than I was, how old? She must have been 11 or 12. She couldn’t recall a time when she hadn't been in that metallic tube.

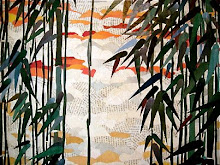

She would ask me to peek at the window and describe to her what I saw. Were there trees? What did they look like? And cars? How big were they? Did they go fast? What was their color? And the people inside, how many? Could I see how they were dressed?

I think I was 4 or 5, it isn’t clear in my mind. I lived with Helene everyday - for weeks or months, I can’t remember.

Helene was my friend. Never upset. Always soft spoken. Very talkative. She never even seemed to realize I couldn't understand everything she said.

I felt an extreme responsibility towards her. A descriptive one because it was my job to narrate; my duty to render the world as concretely as possible so she could picture it in that head of hers, the only part of her body visible and able to move.

I felt so frustrated not to have all the needed words to properly talk of the sky, the clouds, the plants. I knew I was limited, incompetent, that I lacked the vocabulary Helene would have deserved.

I would speak slowly, trying to notice details, searching in my mind for the names I could give to the things I saw.

It was terribly difficult, my sweet one. I wasn’t sufficiently prepared. I felt ashamed. But I did try, with scarce mental resources, to comply with her wishes. You see, I couldn’t use comparisons. Helene had no points of reference besides the steel apparatus that surrounded her.

I had to be careful how I would describe. The wrong expression and Helene’s desire to know more would quickly skid in all directions while she tried to shape coherent images in her mind. And I would find myself unable to follow her in the mysterious ways she used to build her impressions of the world.

Oh, sweet one, it was so complicated.

Helene had only me. Neither of us had visitors. Her, because she had been in the hospital for so long, people had forgotten her. Me, because my family lived out of town.

I had purpura, a blood disease, hemorrhagic, always in danger of endless internal bleeding if I fell or hit myself (explaining why I had never been offered a skipping rope, I guess).

Putting me next to Helene who couldn’t go anywhere, nurses and doctors had made sure I wouldn’t have any accidents or be tempted to run, play, climb with others.

So here we were, Helene and me, day after day, constructing deficient verbal portraits of the streets, landscape, events. Me, suffering from my inability to be limpid, precise, logical, organized in my depictions. Helen, avid of constantly more accurate descriptions. I was terribly aware of my shortcomings. Profoundly frustrated. Damned, I didn’t even know how to read. And I loved Helene so.

One morning, little one, the sound of a mop being hit against furniture woke me up. It was very early, hardly any light around. There was an old man in the room, pushing a gray bucket, spreading soapy water on the floor, cleaning… where Helen’s artificial lung should have been.

She was gone, baby. Totally gone.

I only remember the fear, overwhelming, that took me from head to toe, emptying in its trajectory my entire bowels. I sank so fast, deep into the earth’s dark entrails. It was horrible.

Maybe to help me recover, maybe to keep me company, I was given a large doll. She was as tall as I was. I mean we were truly the exact same size. But where I was angular and skinny, the doll was plump. Her hair was golden, shiny and long; mine was black, short and uncombed. My eyes were brown, hers were blue. I named her, of course, Helene.

The doll shared my bed. I would practice all day long trying to look like her (since I still wasn’t allowed to play outside the room). The first thing to do was to be immobile, parallel to her. I had it to perfection.

As a matter of fact, whenever the doctors made their rounds and came to examine me, they would get it wrong and put their stethoscope on the doll. I thought I was so funny, giggling, hidden under my blankets while they thought Helene was the patient.

When the time came, one day, for my parents to take me back home, where I would still have to remain in bed for months, I asked them not to forget to take Helene with us.

I yelled. I yelled and I yelled, out of my mind, when I realized they hadn’t done so.

My mother, impatient with my hysterical fit, shouted back that there was no doll. She lied, sweetheart. Oh, she lied. I still know it today, old like I am, with all I’ve seen on this planet. That my mother lied. And I immediately planted a large sharp symbolic stick into my heart to make it hurt forever, to never forget my rage.

You may think this is a childish story about a lost toy. About a capricious daughter going nuts on account of a puerile fantasy. Maybe it is. I don’t know how to reply.

To summarize, I ended up starting school late, ignorant about rope skipping, equipped with strange looking nutrients in my lunchbox. Altogether, it’s not such a tragedy.

But neither of the two Helenes of my life had had per se fingerprints. Looking back, that’s where the problem may have been: There’s no way I can formally have either of them identified.

Ciao, Laolao

Towards the end of the 50s, my mother had already started her long quest that would lead decades later to her deep involvement in alternative medicines, new age practices, cults, and concerns over invasions by extraterrestrials.

The beginning of that long journey was with vegetarianism, and it often translated itself by the insertion of yogurt into the lunchbox I brought to school. Yogurt, in those days, wasn’t sold in supermarkets. No one in the suburb where we lived had ever heard about it.

I’m in primary school and in the large cafeteria where we all eat, I must put the warm liquefied yogurt on the table that I share with the other children from my group.

Rotten milk, vomit were among the names that flew around me as I tried to eat. The children would even cross the entire room to come and see how disgusting my lunch was, calling more classmates over to make sure I would really feel uncomfortable. And hate my mother even more for doing this to me.

That’s the moment when I knew I had a selfhood, a oneness that distinguished me completely from others.

After lunch, we all went outside to play in the schoolyard. The kids had skipping ropes and they would do elaborate tricks, jumping as two long colored ropes drew circles in the air without ever touching.

I had never seen a skipping rope before attending school. It was a sort of magical game that everyone knew about, except me. Again, it confirmed my sense of uniqueness.

I didn’t know where they had learned these tricks. Where was I when it had happened? When the instructions on how to jump had been given - the rope under the feet, then over the head, turning so fast?

I remember, little one. I was sick, at Ste-Justine’s Hospital for children. In a room with another girl, Helene.

Helene, who had suffered from polio at a young age, had her entire body in a long silver cylinder, an artificial lung. Only her head could be seen, her hair and face sticking out, turned towards me as we made conversation.

She was much older than I was, how old? She must have been 11 or 12. She couldn’t recall a time when she hadn't been in that metallic tube.

She would ask me to peek at the window and describe to her what I saw. Were there trees? What did they look like? And cars? How big were they? Did they go fast? What was their color? And the people inside, how many? Could I see how they were dressed?

I think I was 4 or 5, it isn’t clear in my mind. I lived with Helene everyday - for weeks or months, I can’t remember.

Helene was my friend. Never upset. Always soft spoken. Very talkative. She never even seemed to realize I couldn't understand everything she said.

I felt an extreme responsibility towards her. A descriptive one because it was my job to narrate; my duty to render the world as concretely as possible so she could picture it in that head of hers, the only part of her body visible and able to move.

I felt so frustrated not to have all the needed words to properly talk of the sky, the clouds, the plants. I knew I was limited, incompetent, that I lacked the vocabulary Helene would have deserved.

I would speak slowly, trying to notice details, searching in my mind for the names I could give to the things I saw.

It was terribly difficult, my sweet one. I wasn’t sufficiently prepared. I felt ashamed. But I did try, with scarce mental resources, to comply with her wishes. You see, I couldn’t use comparisons. Helene had no points of reference besides the steel apparatus that surrounded her.

I had to be careful how I would describe. The wrong expression and Helene’s desire to know more would quickly skid in all directions while she tried to shape coherent images in her mind. And I would find myself unable to follow her in the mysterious ways she used to build her impressions of the world.

Oh, sweet one, it was so complicated.

Helene had only me. Neither of us had visitors. Her, because she had been in the hospital for so long, people had forgotten her. Me, because my family lived out of town.

I had purpura, a blood disease, hemorrhagic, always in danger of endless internal bleeding if I fell or hit myself (explaining why I had never been offered a skipping rope, I guess).

Putting me next to Helene who couldn’t go anywhere, nurses and doctors had made sure I wouldn’t have any accidents or be tempted to run, play, climb with others.

So here we were, Helene and me, day after day, constructing deficient verbal portraits of the streets, landscape, events. Me, suffering from my inability to be limpid, precise, logical, organized in my depictions. Helen, avid of constantly more accurate descriptions. I was terribly aware of my shortcomings. Profoundly frustrated. Damned, I didn’t even know how to read. And I loved Helene so.

One morning, little one, the sound of a mop being hit against furniture woke me up. It was very early, hardly any light around. There was an old man in the room, pushing a gray bucket, spreading soapy water on the floor, cleaning… where Helen’s artificial lung should have been.

She was gone, baby. Totally gone.

I only remember the fear, overwhelming, that took me from head to toe, emptying in its trajectory my entire bowels. I sank so fast, deep into the earth’s dark entrails. It was horrible.

Maybe to help me recover, maybe to keep me company, I was given a large doll. She was as tall as I was. I mean we were truly the exact same size. But where I was angular and skinny, the doll was plump. Her hair was golden, shiny and long; mine was black, short and uncombed. My eyes were brown, hers were blue. I named her, of course, Helene.

The doll shared my bed. I would practice all day long trying to look like her (since I still wasn’t allowed to play outside the room). The first thing to do was to be immobile, parallel to her. I had it to perfection.

As a matter of fact, whenever the doctors made their rounds and came to examine me, they would get it wrong and put their stethoscope on the doll. I thought I was so funny, giggling, hidden under my blankets while they thought Helene was the patient.

When the time came, one day, for my parents to take me back home, where I would still have to remain in bed for months, I asked them not to forget to take Helene with us.

I yelled. I yelled and I yelled, out of my mind, when I realized they hadn’t done so.

My mother, impatient with my hysterical fit, shouted back that there was no doll. She lied, sweetheart. Oh, she lied. I still know it today, old like I am, with all I’ve seen on this planet. That my mother lied. And I immediately planted a large sharp symbolic stick into my heart to make it hurt forever, to never forget my rage.

You may think this is a childish story about a lost toy. About a capricious daughter going nuts on account of a puerile fantasy. Maybe it is. I don’t know how to reply.

To summarize, I ended up starting school late, ignorant about rope skipping, equipped with strange looking nutrients in my lunchbox. Altogether, it’s not such a tragedy.

But neither of the two Helenes of my life had had per se fingerprints. Looking back, that’s where the problem may have been: There’s no way I can formally have either of them identified.

Ciao, Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)