I’m at my piano lesson, after class. All the children have gone home. I feel so fine.

I’ve already been withdrawn from ballet classes offered on weekends because my mother one day arrived early, saw me stretch an arm behind my back, grab my foot, bringing it way over my head so to touch my nose with my big toe. She freaked. Hysterically accused the ballet teacher of imposing torturous moves on poor helpless children. They showed her the door; I had no choice but to follow.

I’m at my piano lesson now, not so much trying to learn how to play, but hoping the required discipline will sink in. Sure, I can already play by ear simple melodies heard on the radio, but I can’t position my hands properly. I'm being taught here to imagine an apple under my palm, but after a while, my hands inevitably flatten as I play.

To remind me of the correct position, the teacher has a long thin stick with which she slightly taps my hands whenever they lose their tonus. I'm applying myself with great care.

And my mother again comes in early, sees a whip, and goes ballistic. This time, I was not only withdrawn from the lessons, I was instantly extracted from the entire school itself.

So here I am at home, no school to go to for a while. My mother drunk-asleep at 11 in the morning. And I’m terribly depressed, the certainty I’ll never be allowed to learn anything.

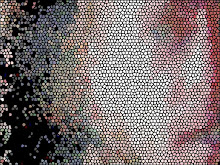

I had a paranoid habit back then. If I deeply liked an object, or if I considered something to be of great importance, exemplary, commendable to posterity, the only way to keep it, did I honestly believe, was to feign indifference towards it. I had convinced myself that every thing I cared for, be it a book, or a pretty scarf, it would mysteriously disappear the minute I would show any form of attachment.

I could only protect whatever I needed by putting a considerable distance between the object and myself, watching it from afar.

To confuse and trick fate, I would pay attention to things that left me indifferent, giving them away, sacrificing them as a way to shield, under this clever pretense, what I cared for the most.

Such a tactic was extremely hard to maintain on a steady basis. It required tremendous strength of character. A will beyond what a child would normally want to handle. A powerful determination, a focus unauthorized to falter.

Every iota of a second involved in a match against destiny, obsessed with the idea of winning for the sake of what was worthy of my loyalty.

Thus, I was the hero of my favorite sweater because I never wore it, of a passionate novel because I would never be seen reading it, of a dozen pictures cut from magazines because I would never look at them. Everyday they all survived on account of my well-hidden, secret devotion.

I would read in bed the evening, putting on my night table before I fell asleep some work I had no feelings for (“The Blue Bird” by Maeterlinck, as an example), sure that soon the book would vanish from our house, no where to be found. And when it happened, I felt so overwhelmingly happy, having ingeniously mislead, defrauded fatality.

I felt I was a genius, my favorite story, “Maroussia, a maid in Ukraine,” safely tuck away as if no one had any interest in it.

You probably think I was obsessed with dispossession. You’re absolutely right. I was maniacally worried.

It’s in that state of mind that I was sent, eventually, to a new school located in a beautiful old building facing the river. The playground had apple trees on which to climb, rows of tall poplars shining on breezy sunny days, intense lilac in the spring.

It was a primary school conceived around the new pedagogical approaches devised in the footsteps of the Summerhill experiment. Everything about freedom, creativity, self-expression.

Many teachers, most of them Europeans. Nourishing my imagination with stories from the war. Building us into the fighters of the future so that never fascism would rise again.

Only one Canadian teacher. He befriended my parents. Came for coffee a few times, impressed by our very own in-house psychologist; my father and the teacher both loudly lauding their modern openness to revolutionary methods in education, their pioneer intellectual stance, their undiluted belief in the spontaneous happiness of the Child.

I did say it. That the creepy local teacher kept me after school to put his hands in my panties. He did so to other girls too.

What happened when I spoke? I remember being so scared of doing so. I had practiced in my mind every word I had to pronounce, afraid to become confused, afraid my mind would go blank as it often did under pressure. I had carefully rehearsed, wanting to do things right.

I recall my preparation, the courage I had gathered, repeating to myself it had to be done. Boosting my resolve thinking I would be the one to denounce him. Walking into the living room, terrified at what I was about to do. Stunned, as I see them oddly perched on ridiculously uncomfortable seats, the two men involved in their self-congratulatory monologues. My mother, an Nth glass of wine in her hand, the smile of beatitude on her face, acquiescing to everything they said.

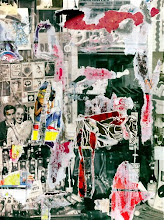

I'm first staring at the tableau, the feeling of familiar unreality back again. The images are standing at the end of a long optical tube. Before I can reach this portrait of pedantic mannerism that's hanging in the living room, there's a tunnel of dark coldness awaiting to be crossed. A zone of black ice, where dematerialization proceeds, sharp crystals in lieu of warm blood, frozen ash floating away from me.

Then, like an automaton, I opened my mouth, a miracle and the sound came out. I spoke. I said it. And then, the memory ends. I don’t know what happened after that. Except for a lingering: the vertiginous stench of shame.

I was kept in that school for six more years, as was the pervert. To distract my mind, I entertained myself climbing trees to catch a glimpse of the horizon, sharpening my skills at spotting fascists. Safe from piano and ballet.

With time, I came to dementedly despise the posh, aerodynamic Scandinavian-style teak furniture typical of the suburban sixties my parents had bought for the living room. Because they gloated about it the same way, with the same kind of shallow pride they used when talking about their sophisticated far advanced avant-garde views on how to raise children.

On the last page of the book, Maroussia, in the prime of her youth is shot to death while running through a bright yellow field of undulating wheat florets.

A red flower springs to life where her head, a crimson-colored scarf to hold her golden hair, hits the ground.

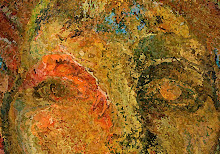

Written in the 19th century by Marko Vovchok, a pseudonym for the well-hidden name of Mariia Vilinska, the tale belongs to Ukrainian folk stories where the predicaments of young women find their way into the traits of brave, but ill-fated romantic heroines. Peasant girls crushed by serfdom or victims of intestine wars, unable to escape their plight like the one epitomized, in my own personal legend, by the stylish pieces of Scandinavian furniture that polluted my childhood's decor.

My triumph perfectly concealed, the story I've just told you never taken away from me, as no one would ever see me, would ever catch me turning the page.

Laolao

I’ve already been withdrawn from ballet classes offered on weekends because my mother one day arrived early, saw me stretch an arm behind my back, grab my foot, bringing it way over my head so to touch my nose with my big toe. She freaked. Hysterically accused the ballet teacher of imposing torturous moves on poor helpless children. They showed her the door; I had no choice but to follow.

I’m at my piano lesson now, not so much trying to learn how to play, but hoping the required discipline will sink in. Sure, I can already play by ear simple melodies heard on the radio, but I can’t position my hands properly. I'm being taught here to imagine an apple under my palm, but after a while, my hands inevitably flatten as I play.

To remind me of the correct position, the teacher has a long thin stick with which she slightly taps my hands whenever they lose their tonus. I'm applying myself with great care.

And my mother again comes in early, sees a whip, and goes ballistic. This time, I was not only withdrawn from the lessons, I was instantly extracted from the entire school itself.

So here I am at home, no school to go to for a while. My mother drunk-asleep at 11 in the morning. And I’m terribly depressed, the certainty I’ll never be allowed to learn anything.

I had a paranoid habit back then. If I deeply liked an object, or if I considered something to be of great importance, exemplary, commendable to posterity, the only way to keep it, did I honestly believe, was to feign indifference towards it. I had convinced myself that every thing I cared for, be it a book, or a pretty scarf, it would mysteriously disappear the minute I would show any form of attachment.

I could only protect whatever I needed by putting a considerable distance between the object and myself, watching it from afar.

To confuse and trick fate, I would pay attention to things that left me indifferent, giving them away, sacrificing them as a way to shield, under this clever pretense, what I cared for the most.

Such a tactic was extremely hard to maintain on a steady basis. It required tremendous strength of character. A will beyond what a child would normally want to handle. A powerful determination, a focus unauthorized to falter.

Every iota of a second involved in a match against destiny, obsessed with the idea of winning for the sake of what was worthy of my loyalty.

Thus, I was the hero of my favorite sweater because I never wore it, of a passionate novel because I would never be seen reading it, of a dozen pictures cut from magazines because I would never look at them. Everyday they all survived on account of my well-hidden, secret devotion.

I would read in bed the evening, putting on my night table before I fell asleep some work I had no feelings for (“The Blue Bird” by Maeterlinck, as an example), sure that soon the book would vanish from our house, no where to be found. And when it happened, I felt so overwhelmingly happy, having ingeniously mislead, defrauded fatality.

I felt I was a genius, my favorite story, “Maroussia, a maid in Ukraine,” safely tuck away as if no one had any interest in it.

You probably think I was obsessed with dispossession. You’re absolutely right. I was maniacally worried.

It’s in that state of mind that I was sent, eventually, to a new school located in a beautiful old building facing the river. The playground had apple trees on which to climb, rows of tall poplars shining on breezy sunny days, intense lilac in the spring.

It was a primary school conceived around the new pedagogical approaches devised in the footsteps of the Summerhill experiment. Everything about freedom, creativity, self-expression.

Many teachers, most of them Europeans. Nourishing my imagination with stories from the war. Building us into the fighters of the future so that never fascism would rise again.

Only one Canadian teacher. He befriended my parents. Came for coffee a few times, impressed by our very own in-house psychologist; my father and the teacher both loudly lauding their modern openness to revolutionary methods in education, their pioneer intellectual stance, their undiluted belief in the spontaneous happiness of the Child.

I did say it. That the creepy local teacher kept me after school to put his hands in my panties. He did so to other girls too.

What happened when I spoke? I remember being so scared of doing so. I had practiced in my mind every word I had to pronounce, afraid to become confused, afraid my mind would go blank as it often did under pressure. I had carefully rehearsed, wanting to do things right.

I recall my preparation, the courage I had gathered, repeating to myself it had to be done. Boosting my resolve thinking I would be the one to denounce him. Walking into the living room, terrified at what I was about to do. Stunned, as I see them oddly perched on ridiculously uncomfortable seats, the two men involved in their self-congratulatory monologues. My mother, an Nth glass of wine in her hand, the smile of beatitude on her face, acquiescing to everything they said.

I'm first staring at the tableau, the feeling of familiar unreality back again. The images are standing at the end of a long optical tube. Before I can reach this portrait of pedantic mannerism that's hanging in the living room, there's a tunnel of dark coldness awaiting to be crossed. A zone of black ice, where dematerialization proceeds, sharp crystals in lieu of warm blood, frozen ash floating away from me.

Then, like an automaton, I opened my mouth, a miracle and the sound came out. I spoke. I said it. And then, the memory ends. I don’t know what happened after that. Except for a lingering: the vertiginous stench of shame.

I was kept in that school for six more years, as was the pervert. To distract my mind, I entertained myself climbing trees to catch a glimpse of the horizon, sharpening my skills at spotting fascists. Safe from piano and ballet.

With time, I came to dementedly despise the posh, aerodynamic Scandinavian-style teak furniture typical of the suburban sixties my parents had bought for the living room. Because they gloated about it the same way, with the same kind of shallow pride they used when talking about their sophisticated far advanced avant-garde views on how to raise children.

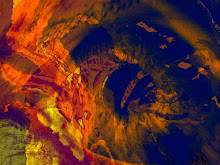

On the last page of the book, Maroussia, in the prime of her youth is shot to death while running through a bright yellow field of undulating wheat florets.

A red flower springs to life where her head, a crimson-colored scarf to hold her golden hair, hits the ground.

Written in the 19th century by Marko Vovchok, a pseudonym for the well-hidden name of Mariia Vilinska, the tale belongs to Ukrainian folk stories where the predicaments of young women find their way into the traits of brave, but ill-fated romantic heroines. Peasant girls crushed by serfdom or victims of intestine wars, unable to escape their plight like the one epitomized, in my own personal legend, by the stylish pieces of Scandinavian furniture that polluted my childhood's decor.

My triumph perfectly concealed, the story I've just told you never taken away from me, as no one would ever see me, would ever catch me turning the page.

Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment