I think it’s time. I must tell you something about myself that nobody knows, something I’ve always been extremely ashamed of. Something I’ve kept secret. You can’t start to understand the meaning of the word secret until you can fathom how deep and absolute mine has been until today.

Of course, any secret, even as protected and hidden as the one I had, manages at times to leave hints, traces of itself on the surface of the world, showing how impossible it is to control it in its entirety.

It has happened. Moments when I would realize after the fact, and too late, that outside of my will the secret had manifested itself, printing an indelible mark that could give its substance away. A dangerous clue with the potential to lead people to that secret.

If they added one plus one, they would get to two. I knew that. And I watched, powerless, with a terrible, heavy anxiety to see if anyone would do the math and figure out what I thought had no right to be said and known about me.

But I’m also full of contradictions. Acutely aware of them as if a gambler by nature, perhaps a part of me wanting others to find out. Playing with fire. Gradually becoming bolder. Testing. Liking probably the extreme fear that came along the game I ended up designing.

In short, I did everything that was humanly possible to lock up the secret, but I also exposed myself to the very environments that had what it took to uncover what I worked so hard at camouflaging. Masochism? I guess. In part at least. The other part being a strategy. Understanding quite early on that absolute denial and pretense would fail. I needed in order to reach my goal a certain balance between suppressing the content of the secret and developing a familiarity with it. Only then would an efficient exercise at control be achieved.

So, as indications of my secret popped up here and there despite my constant efforts to tame them, I also ventured further into areas where the risks of being discovered were great, thus forcing me to reinforce my hideout. This is how, oh irony, step by step, very slowly, I ended up one day completely living in the environment I feared the most.

You recall that I was told, as a teenager, that I would never be able to study. During my first and second hospitalizations in a psychiatric ward, I was submitted to extensive tests, psychological as well as neurological. A combination of problems was identified. They were not all explained to me. But some were.

I remember a doctor calling me to his office one afternoon, and calmly laying out the facts.

He did not really elaborate on the various diagnoses. He was more concerned by the fact that my parents had rejected what he had tried to tell them, categorically refusing to hear him out.

He offered me a solution: The hospital would, if I accepted, represent me in a legal request, since I was a minor, to put myself under the protection of the state, asking to be placed in a specialized institution or foster home able to deal with my condition.

I refused.

How would my life have been, what kind of person would I have become, who would I be today if I had said yes? I have no idea. Would it all have been easier? Worst? I can’t tell. But there hasn’t been a day since where I haven’t wondered about the possible outcomes of a different decision. I’ll never know.

They did not find any neurological causes, I was told, to my problems. They had been worried, among other things, that the purpura I had suffered from as a child could have left scars in the brain, but apparently it didn’t. Even more extensive tests done later in my life confirmed this.

Family history did not support either the hypothesis that my condition was genetic. I seemed to be the only one stuck with the problem.

At that point there were no other causes known but a psychological one to explain what was going on. Nevertheless, the team of specialists had concluded that the problems were incurable, too deep and severe to be reversed. With proper care, I would perhaps be able to learn how to cope with some of them, but never to the extent of allowing me a normal life.

I had an IQ well over 130, I was informed. My intelligence not put into question. My impediments having nothing to do with my comprehension.

Of course, some of what was said to me on that day was no surprise. My behavioral peculiarities were obvious. I had figured that much by myself. But the doctor added to that awareness the name of a serious handicap I hadn’t seen coming.

Up to that moment, I had not considered the symptoms as separate. Instinctively, I had always approached them as another expression of my screwed-up personality, meaning not as a distinct issue. So the news came as a real blow. Totally unexpected, and painful.

I was so profoundly dyslexic, it was explained to me, that even with coping mechanisms I would never be able to study. Had to give up the idea of even finishing high school unless I went to a special one for people like me. But to go to such an institution, I would have to be extracted from my family via a request for new legal guardians.

Remember, I said no.

I disliked my family. I didn’t reject the proposal out of affection for my parents or a longing for my siblings. No. I did it mainly because the opinion I had, at that time, of a family was so negative that this one or another, in my mind, would still be a source of conflicts. I had so little trust in adults that I couldn’t imagine other people to be any better or helpful than those I already knew.

For me, survival was the key issue. How does one protect oneself from strangers? Difficult. Whereas on familiar grounds, I thought I could better manage, I answered the doctor.

I had always been alone while struggling. I couldn’t conceive letting others in as participants. Intuitively, I perceived such an inclusion as a possible annoyance, with the potential even to become a danger to me. I faced an extremely intimate situation. There was no room anyway in there for another person.

Might as well go back, I thought, to an environment where the sum of my experiences could be relied upon as guidelines to sustain myself. Where I had some knowledge, defective maybe, - but that was much more desirable than none at all. That's what I said. It made sense. Among other things I was dyslexic, yes, but not dumb.

I also figured that being told my family, if I wanted to, could be eliminated from my life was in itself sufficient information. It would allow me to see myself “officially” as not truly belonging there, a card up my sleeve in case later it would be needed. I would go back there on my own free will, not because I had to or was forced to. That fact introduced an important difference. It gave me some kind of leverage.

Up to the minute when my father died, when my mother died, I have been thoroughly aware that I stood next to them only because I was the one who had decided to. Not them. It took away all their powers. When in the last moments of my mother’s life, as an example, everybody ran away, busy doing something else, I stood all by myself watching her die, and I was able to go through with it, unlike the rest of the family members, because I had consciously decided to. Not because of guilt. Not because she had no one else. Not because she wanted to or asked me to. But because I had had a long, long practice at making such decisions. It had started almost 30 years earlier, the day I was informed of my dyslexia.

Now, you’ll ask. How can a deep dyslexic become an avid reader and nourish dreams of becoming a writer? How can such a person be fascinated by languages other than the one already said to be impossible to fully handle for that person? Well, lets call it for now the funny part.

The truth is: This mystery lends itself quite well to an explanation. Be patient. I’ll come to that later. But the one that remains has to do with the secrecy others have also unilaterally woven around my condition. True, I never discussed it. But neither did my parents. Not once. Not even pronouncing in my presence the word itself. Not the slightest allusion ever. As if it did not exist. I don’t even think my sisters or relatives were made aware of my handicap. It’s as if my parents had never been told or had never realized the nature of my plight. That’s quite an accomplishment…

But the doctor did confirm he had met them to discuss the issue. He clearly said so. And he added they had reacted quite negatively. They had stormed out. Left. The only explanation I can think of is that when my parents understood the direction the specialist was heading for, they got scared and simply ran away, not hearing the rest. They only had, therefore, partial information. They didn’t give sufficient time to the doctor to fully detail the situation. And afterwards, they succeeded in erasing the few bits thrown at them. They never had a full measure of the context. So it was relatively easy for them to forget about it. Or pretend to. Or convince themselves it was something else.

My father being a psychologist probably made that possible. He had enough theoretical knowledge to twist whatever he didn’t want to recognize into something unrecognizable. Using his authority in the field, I can well imagine how he instantly developed counter-arguments to undo the damage made to his pride. And my mother might have been happy to position herself behind the tone of expertise my father must have displayed. And I gather he did so with a sort of desperate energy killing in the bud all potential for disagreements.

We’ll never know for sure how they succeeded in obliterating such crucial information about their eldest child.

But lets go back again to that day I was told I would never be able to study. Here’s something we can deal with.

For now, what I need to say is how I felt. It’s not going to take long. My feeling was so monolithic. No ambiguity about it whatsoever. A massive, non-equivocal emotional reaction: It was an imperious, commanding anger.

The type of anger no one should ever get to experience. So overwhelming that the odds of recovering from it were almost nil. An anger beyond measurability. I did not scream. I did not move. I did not protest. I did not argue. Why? Because it was impossible to express even a tiny portion of how I felt. That door could not be opened. The destructiveness of my feeling could not even for a single instant be doubted. An anger intensely immediate and eternal. Infinity. No boundaries. No limits. No end to it. An interminable depth. Anger like you cannot imagine.

Raw hatred and anger.

So large, so powerful that it had no target. Everything the universe is and can be was in my feeling. It englobed it all. A magnitude that left nothing out.

It could have totally consumed me, kill me as it later almost did. Or with its amazing violence destroy the course of the prognosis. But on that very day, I didn’t know yet which way sheer hatred and anger would go.

I was in that hospital to get help. Not to be told none was available. Not to be made aware at 15 years old that my hopes, my desires, my entire future were absolutely nothing.

I’m sitting in front of the doctor, and I fully understand that this idea of sending me to a special place is a palliative solution. Not a remedy. It would not make the problems disappear. He said so. On the contrary. It would confirm, cement them. It makes no sense. This is essentially an unacceptable situation. Dyslexia is an utterly unfair state of my affairs. No fuckin’ way. If I go down, the world comes down with me. That’s a promise. I swear to it.

My parents may chose to forgo their responsibility to help me, they may relinquish their status as capable caregivers, surrender their aspirations to act as decent people, but I won’t. I’m not letting this be. I’m gonna piss them off forever. That’s my decision. And EVERYBODY is wrong about me. This family or another family, no difference. And I hate all of you. I’ll beat you. I’ll bulldoze you. My anger is so formidable that none of you will resist its impact. I’m standing my ground, imbued with this gigantic anger, and I’m not letting any shred of it go. My parents walked away? Fine. I know where they live and that’s where I’m heading. And no one will stop me. And I’ll prove, a 100% proof, that all of you, without a single exception, you’re absolute assholes. I’m even ready to die if I’m sure it punishes you the way you deserve. If it annihilates you, your stupidity and selfishness. I will not let you free for one second. I will not let you spread your ineptitudes and idiocy. I, me, the impaired, the doomed, I will get you. I will win. I will devote until my last breath the totality of my hatred, of my anger at ascertaining my point. You will not live a quiet life, none of you, in the land of I-can-pretend-there’s-no-problem. You will never be relieved of my presence. You will die, and I will be there. When everyone else will have abandoned you, I will still be there. And you will look into my eyes, the last thing you see, and you will know.

This is exactly how I’m thinking in silence in that doctor’s office. A placid composure like a magnificent, brilliant and crazy strategy. Not a gesture out of place. Not a movement of my eyelid to betray the incredible mass of my plan. Wait until it hits all of you. I’ll level your world. I’m the one who prevails. Not your attitudes, not your decisions, not your attempts at running away. Look. Cuckoo… it’s me. You, fuckers.

Do you have any idea of how many schools I had gone to, ending up not going to school at all? My parents always playing the prima donna, carried by an inflated view of their importance, constantly blaming others. Two educated, wealthy adults ready to sacrifice me so not to admit I had learning disabilities. Categorically refusing even to discuss these, preserving a chimera about their image and competencies. I was so pissed.

Don’t let any of what I’m saying fool you though. That’s the secret I’m revealing today. I am still highly dyslexic. Every second of my life. If you pay very close attention, you’ll spot the signs of what, at times, I fail to master, what escapes my obsessive techniques at countering dreadful deficiencies. Or you’ll notice my tiredness. Because it’s exhausting beyond description to constantly be on guard against the very essence of my own brain.

Since I have never told anyone about my dyslexia, my children have never known about it either. Of course, they made fun of my weird ways of doing things at times, argued or joked about peculiarities, my “forgetfulness,” perhaps my absent-mindedness to account for mistakes. But it was friendly, kind. Never hinting at the presence of a more severe condition. In fact, no one ever realized the extent of my misery.

But I must say now how all those years I have been terrified to somehow transmit the problem to my kids. How I’ve carefully watched over them, extremely attentive for any sign that would have indicated that my disability was shared. Whenever my children at school had periods where they were either difficult students or exhibited behavior considered troublesome, I spent sleepless nights worrying about the possibility that they might too be dyslexic. I consulted. Went over the various criteria. Talked to teachers. Examined their assignments until I was sure whatever issue was at stake had nothing to do with what I had. In the light of my own condition, I thought (mistakenly maybe) that anything else was preferable. And could somehow be remedied.

Looking back, I was wrong not to tell anyone of the cause of my fear. But believe me, I honestly didn’t think I had a choice.

My daughter recently introduced me to a friend of hers. She had told me just before he arrived that this engineer was dyslexic. And it dawned on me. What? This can be said, just like that?

Through this anonymous post today I apologize to my children. And to everyone. Unable still to do it face-to-face though. I know I’m a coward. Unable yet to untangle the past and all the barriers I’ve set up.

Even in old age, I continue to feel that if I went about revealing the truth any other way than obliquely, all the systems I’ve built to function in society would crumble. And they would do so for one reason: If I were ever to pronounce the words, I know with certainty that I would cry, and would never stop crying after that, possibly harming everything and all relationships I’ve been able to build over the years.

From the bottom of my heart, from the place in me that is not stained by any ordeal, that remains genuine and purely translucent, where my love for you is the only thing that exists, I ask for your forgiveness.

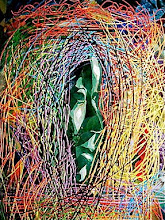

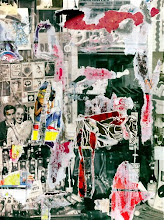

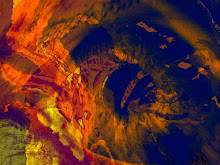

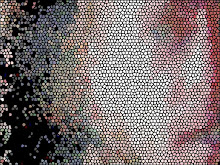

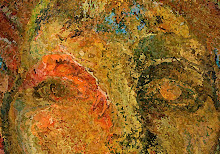

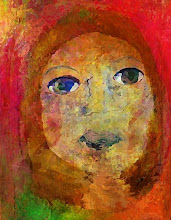

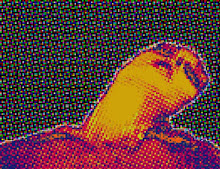

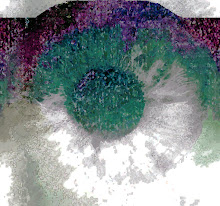

To help you understand and accept, know that every collage I ever did, just to name that, has been an effort at honesty. In them, I disclose how I proceed to subdue my dyslexia. They all are a meticulous representation of a fairly effective methodology to thrive and be with you.

And, ironically, I’ve learned to appreciate the mistakes they contain in spite of my dedication to preventing such clues from appearing. This way I’m not a complete lie. And I can smile, a truly happy smile.

That's what art is all about, baby. The imperfections that resist and outlast paramount battles, asserting their rightful and meaningful place.

Laolao

Of course, any secret, even as protected and hidden as the one I had, manages at times to leave hints, traces of itself on the surface of the world, showing how impossible it is to control it in its entirety.

It has happened. Moments when I would realize after the fact, and too late, that outside of my will the secret had manifested itself, printing an indelible mark that could give its substance away. A dangerous clue with the potential to lead people to that secret.

If they added one plus one, they would get to two. I knew that. And I watched, powerless, with a terrible, heavy anxiety to see if anyone would do the math and figure out what I thought had no right to be said and known about me.

But I’m also full of contradictions. Acutely aware of them as if a gambler by nature, perhaps a part of me wanting others to find out. Playing with fire. Gradually becoming bolder. Testing. Liking probably the extreme fear that came along the game I ended up designing.

In short, I did everything that was humanly possible to lock up the secret, but I also exposed myself to the very environments that had what it took to uncover what I worked so hard at camouflaging. Masochism? I guess. In part at least. The other part being a strategy. Understanding quite early on that absolute denial and pretense would fail. I needed in order to reach my goal a certain balance between suppressing the content of the secret and developing a familiarity with it. Only then would an efficient exercise at control be achieved.

So, as indications of my secret popped up here and there despite my constant efforts to tame them, I also ventured further into areas where the risks of being discovered were great, thus forcing me to reinforce my hideout. This is how, oh irony, step by step, very slowly, I ended up one day completely living in the environment I feared the most.

You recall that I was told, as a teenager, that I would never be able to study. During my first and second hospitalizations in a psychiatric ward, I was submitted to extensive tests, psychological as well as neurological. A combination of problems was identified. They were not all explained to me. But some were.

I remember a doctor calling me to his office one afternoon, and calmly laying out the facts.

He did not really elaborate on the various diagnoses. He was more concerned by the fact that my parents had rejected what he had tried to tell them, categorically refusing to hear him out.

He offered me a solution: The hospital would, if I accepted, represent me in a legal request, since I was a minor, to put myself under the protection of the state, asking to be placed in a specialized institution or foster home able to deal with my condition.

I refused.

How would my life have been, what kind of person would I have become, who would I be today if I had said yes? I have no idea. Would it all have been easier? Worst? I can’t tell. But there hasn’t been a day since where I haven’t wondered about the possible outcomes of a different decision. I’ll never know.

They did not find any neurological causes, I was told, to my problems. They had been worried, among other things, that the purpura I had suffered from as a child could have left scars in the brain, but apparently it didn’t. Even more extensive tests done later in my life confirmed this.

Family history did not support either the hypothesis that my condition was genetic. I seemed to be the only one stuck with the problem.

At that point there were no other causes known but a psychological one to explain what was going on. Nevertheless, the team of specialists had concluded that the problems were incurable, too deep and severe to be reversed. With proper care, I would perhaps be able to learn how to cope with some of them, but never to the extent of allowing me a normal life.

I had an IQ well over 130, I was informed. My intelligence not put into question. My impediments having nothing to do with my comprehension.

Of course, some of what was said to me on that day was no surprise. My behavioral peculiarities were obvious. I had figured that much by myself. But the doctor added to that awareness the name of a serious handicap I hadn’t seen coming.

Up to that moment, I had not considered the symptoms as separate. Instinctively, I had always approached them as another expression of my screwed-up personality, meaning not as a distinct issue. So the news came as a real blow. Totally unexpected, and painful.

I was so profoundly dyslexic, it was explained to me, that even with coping mechanisms I would never be able to study. Had to give up the idea of even finishing high school unless I went to a special one for people like me. But to go to such an institution, I would have to be extracted from my family via a request for new legal guardians.

Remember, I said no.

I disliked my family. I didn’t reject the proposal out of affection for my parents or a longing for my siblings. No. I did it mainly because the opinion I had, at that time, of a family was so negative that this one or another, in my mind, would still be a source of conflicts. I had so little trust in adults that I couldn’t imagine other people to be any better or helpful than those I already knew.

For me, survival was the key issue. How does one protect oneself from strangers? Difficult. Whereas on familiar grounds, I thought I could better manage, I answered the doctor.

I had always been alone while struggling. I couldn’t conceive letting others in as participants. Intuitively, I perceived such an inclusion as a possible annoyance, with the potential even to become a danger to me. I faced an extremely intimate situation. There was no room anyway in there for another person.

Might as well go back, I thought, to an environment where the sum of my experiences could be relied upon as guidelines to sustain myself. Where I had some knowledge, defective maybe, - but that was much more desirable than none at all. That's what I said. It made sense. Among other things I was dyslexic, yes, but not dumb.

I also figured that being told my family, if I wanted to, could be eliminated from my life was in itself sufficient information. It would allow me to see myself “officially” as not truly belonging there, a card up my sleeve in case later it would be needed. I would go back there on my own free will, not because I had to or was forced to. That fact introduced an important difference. It gave me some kind of leverage.

Up to the minute when my father died, when my mother died, I have been thoroughly aware that I stood next to them only because I was the one who had decided to. Not them. It took away all their powers. When in the last moments of my mother’s life, as an example, everybody ran away, busy doing something else, I stood all by myself watching her die, and I was able to go through with it, unlike the rest of the family members, because I had consciously decided to. Not because of guilt. Not because she had no one else. Not because she wanted to or asked me to. But because I had had a long, long practice at making such decisions. It had started almost 30 years earlier, the day I was informed of my dyslexia.

Now, you’ll ask. How can a deep dyslexic become an avid reader and nourish dreams of becoming a writer? How can such a person be fascinated by languages other than the one already said to be impossible to fully handle for that person? Well, lets call it for now the funny part.

The truth is: This mystery lends itself quite well to an explanation. Be patient. I’ll come to that later. But the one that remains has to do with the secrecy others have also unilaterally woven around my condition. True, I never discussed it. But neither did my parents. Not once. Not even pronouncing in my presence the word itself. Not the slightest allusion ever. As if it did not exist. I don’t even think my sisters or relatives were made aware of my handicap. It’s as if my parents had never been told or had never realized the nature of my plight. That’s quite an accomplishment…

But the doctor did confirm he had met them to discuss the issue. He clearly said so. And he added they had reacted quite negatively. They had stormed out. Left. The only explanation I can think of is that when my parents understood the direction the specialist was heading for, they got scared and simply ran away, not hearing the rest. They only had, therefore, partial information. They didn’t give sufficient time to the doctor to fully detail the situation. And afterwards, they succeeded in erasing the few bits thrown at them. They never had a full measure of the context. So it was relatively easy for them to forget about it. Or pretend to. Or convince themselves it was something else.

My father being a psychologist probably made that possible. He had enough theoretical knowledge to twist whatever he didn’t want to recognize into something unrecognizable. Using his authority in the field, I can well imagine how he instantly developed counter-arguments to undo the damage made to his pride. And my mother might have been happy to position herself behind the tone of expertise my father must have displayed. And I gather he did so with a sort of desperate energy killing in the bud all potential for disagreements.

We’ll never know for sure how they succeeded in obliterating such crucial information about their eldest child.

But lets go back again to that day I was told I would never be able to study. Here’s something we can deal with.

For now, what I need to say is how I felt. It’s not going to take long. My feeling was so monolithic. No ambiguity about it whatsoever. A massive, non-equivocal emotional reaction: It was an imperious, commanding anger.

The type of anger no one should ever get to experience. So overwhelming that the odds of recovering from it were almost nil. An anger beyond measurability. I did not scream. I did not move. I did not protest. I did not argue. Why? Because it was impossible to express even a tiny portion of how I felt. That door could not be opened. The destructiveness of my feeling could not even for a single instant be doubted. An anger intensely immediate and eternal. Infinity. No boundaries. No limits. No end to it. An interminable depth. Anger like you cannot imagine.

Raw hatred and anger.

So large, so powerful that it had no target. Everything the universe is and can be was in my feeling. It englobed it all. A magnitude that left nothing out.

It could have totally consumed me, kill me as it later almost did. Or with its amazing violence destroy the course of the prognosis. But on that very day, I didn’t know yet which way sheer hatred and anger would go.

I was in that hospital to get help. Not to be told none was available. Not to be made aware at 15 years old that my hopes, my desires, my entire future were absolutely nothing.

I’m sitting in front of the doctor, and I fully understand that this idea of sending me to a special place is a palliative solution. Not a remedy. It would not make the problems disappear. He said so. On the contrary. It would confirm, cement them. It makes no sense. This is essentially an unacceptable situation. Dyslexia is an utterly unfair state of my affairs. No fuckin’ way. If I go down, the world comes down with me. That’s a promise. I swear to it.

My parents may chose to forgo their responsibility to help me, they may relinquish their status as capable caregivers, surrender their aspirations to act as decent people, but I won’t. I’m not letting this be. I’m gonna piss them off forever. That’s my decision. And EVERYBODY is wrong about me. This family or another family, no difference. And I hate all of you. I’ll beat you. I’ll bulldoze you. My anger is so formidable that none of you will resist its impact. I’m standing my ground, imbued with this gigantic anger, and I’m not letting any shred of it go. My parents walked away? Fine. I know where they live and that’s where I’m heading. And no one will stop me. And I’ll prove, a 100% proof, that all of you, without a single exception, you’re absolute assholes. I’m even ready to die if I’m sure it punishes you the way you deserve. If it annihilates you, your stupidity and selfishness. I will not let you free for one second. I will not let you spread your ineptitudes and idiocy. I, me, the impaired, the doomed, I will get you. I will win. I will devote until my last breath the totality of my hatred, of my anger at ascertaining my point. You will not live a quiet life, none of you, in the land of I-can-pretend-there’s-no-problem. You will never be relieved of my presence. You will die, and I will be there. When everyone else will have abandoned you, I will still be there. And you will look into my eyes, the last thing you see, and you will know.

This is exactly how I’m thinking in silence in that doctor’s office. A placid composure like a magnificent, brilliant and crazy strategy. Not a gesture out of place. Not a movement of my eyelid to betray the incredible mass of my plan. Wait until it hits all of you. I’ll level your world. I’m the one who prevails. Not your attitudes, not your decisions, not your attempts at running away. Look. Cuckoo… it’s me. You, fuckers.

Do you have any idea of how many schools I had gone to, ending up not going to school at all? My parents always playing the prima donna, carried by an inflated view of their importance, constantly blaming others. Two educated, wealthy adults ready to sacrifice me so not to admit I had learning disabilities. Categorically refusing even to discuss these, preserving a chimera about their image and competencies. I was so pissed.

Don’t let any of what I’m saying fool you though. That’s the secret I’m revealing today. I am still highly dyslexic. Every second of my life. If you pay very close attention, you’ll spot the signs of what, at times, I fail to master, what escapes my obsessive techniques at countering dreadful deficiencies. Or you’ll notice my tiredness. Because it’s exhausting beyond description to constantly be on guard against the very essence of my own brain.

Since I have never told anyone about my dyslexia, my children have never known about it either. Of course, they made fun of my weird ways of doing things at times, argued or joked about peculiarities, my “forgetfulness,” perhaps my absent-mindedness to account for mistakes. But it was friendly, kind. Never hinting at the presence of a more severe condition. In fact, no one ever realized the extent of my misery.

But I must say now how all those years I have been terrified to somehow transmit the problem to my kids. How I’ve carefully watched over them, extremely attentive for any sign that would have indicated that my disability was shared. Whenever my children at school had periods where they were either difficult students or exhibited behavior considered troublesome, I spent sleepless nights worrying about the possibility that they might too be dyslexic. I consulted. Went over the various criteria. Talked to teachers. Examined their assignments until I was sure whatever issue was at stake had nothing to do with what I had. In the light of my own condition, I thought (mistakenly maybe) that anything else was preferable. And could somehow be remedied.

Looking back, I was wrong not to tell anyone of the cause of my fear. But believe me, I honestly didn’t think I had a choice.

My daughter recently introduced me to a friend of hers. She had told me just before he arrived that this engineer was dyslexic. And it dawned on me. What? This can be said, just like that?

Through this anonymous post today I apologize to my children. And to everyone. Unable still to do it face-to-face though. I know I’m a coward. Unable yet to untangle the past and all the barriers I’ve set up.

Even in old age, I continue to feel that if I went about revealing the truth any other way than obliquely, all the systems I’ve built to function in society would crumble. And they would do so for one reason: If I were ever to pronounce the words, I know with certainty that I would cry, and would never stop crying after that, possibly harming everything and all relationships I’ve been able to build over the years.

From the bottom of my heart, from the place in me that is not stained by any ordeal, that remains genuine and purely translucent, where my love for you is the only thing that exists, I ask for your forgiveness.

To help you understand and accept, know that every collage I ever did, just to name that, has been an effort at honesty. In them, I disclose how I proceed to subdue my dyslexia. They all are a meticulous representation of a fairly effective methodology to thrive and be with you.

And, ironically, I’ve learned to appreciate the mistakes they contain in spite of my dedication to preventing such clues from appearing. This way I’m not a complete lie. And I can smile, a truly happy smile.

That's what art is all about, baby. The imperfections that resist and outlast paramount battles, asserting their rightful and meaningful place.

Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment