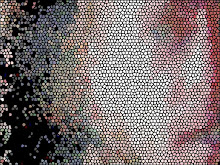

Of course, souvenirs play tricks on us. We remember tensed moments much better than casual ones. Just to name a few, we certainly wouldn’t forget a self-declared martyr posing in front of our eyes, the agony of self-reproach, or any of our psychological needs when they’re thrown off-balance. But when we try to recall being satisfied, the presence of a benevolent mind by our side, the subtle essence of pure understanding, we seem to set the unreal into motion, and fall victims to metaphysical skepticism.

I wish I could tell you I was a happy child. I wish I could describe some fun events without suspicion having to invade the entire domain of my experiences.

Since she was a fashion designer, my mother was entitled to carry around the largest, sharpest scissors you can imagine. They were made of long, heavy blades. Their black handles so large, my hands could almost go through the holes.

She did try a couple of times to stab my father with them. I would be in bed downstairs, listening to my mother’s shouts, the accusations: A mistress here, a venereal disease there, money running out, spent on seduction masquerades. Never heard my father reply. He wept, feeling sorry for himself, working at staying out of reach of the scissors.

I disliked my mother’s outbursts, but I thought she was basically in her right to be pissed. I wished though she would have dropped the scissors. And perhaps my father, on his side, could have helped appease the scene by uttering something like “stop” or "sorry."

The scissors terrified me. They were my mother’s weapon of predilection whenever she ran out of insults. She actually didn’t know that many. Her vocabulary was modest. A thing rather than a flux. So the scissors often came in handy.

Conveniently, I can’t remember how our fight had started: I see my mother’s strong hands tightly squeezing mine around the handles of the scissors. I’m trying to free my fingers without making the scissors jerk. You see, my mother is pulling the scissors towards her stomach. She has the blades against her own body. She yells that I should kill her. As I pull in the opposite direction with all my might, I’m crying ‘Please, stop. Stop this.’

A proof by the way that I was much more articulate than my father.

A million thoughts go through a kid’s mind at such a moment. I can’t free my hands. She’s trying to puncture herself using me as an assassin. And I am so tired, baby, I am hoping that these melodramatic clashes can end right now. What if, for a fraction of a second, I stop pulling the scissors away from her? What if I simply relax my muscles?

Yes, the plan did germinate in my mind. And it’s not love or caring that prevented me from letting my mother fall into her own trap. No. It was a selfish move. I wasn’t sure at which age people could go to jail. At 10, I felt I was already a grown-up person. Who would have believed that my hands on the scissors had been forced?

So I pulled and pulled the scissors away from my mother, saving myself, not her.

My mother would always remind the world that she didn’t have a mother, therefore no role-model for her. She claimed to have done her best under the circumstances. I sort of believe her.

I taught myself to be a mother watching her, and I raised my children equipped with that oblique hint. In turn, they are now educating you, my grand-children, also readied by that history. There’s little I can do to change that, except through theoretical attitudes, unmasking the underground constructions that marked our family’s sub-culture, the dominance-submission rites we savagely danced to.

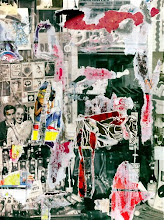

My memories, as you may have noticed, always seem to rise from such manipulative, reified debris.

They’re totally indoctrinated by a sense of ethics born from ancient reaction patterns. Redefined by a world essentially made of testimonials sentenced to destruction.

Sacred dreams of fairness, justice, equality vacillating between denied potentialities and self-proclaimed repression.

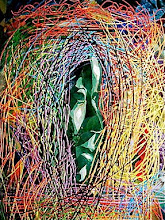

There’s no beam of truth highlighting my childhood souvenirs, no exoskeleton to protect them. Instead, it’s a sort of dissipated, undisciplined holographic light blurring all the way to non-existence formless fears, beyond rescue, sometimes diluting them in a vein of raw senseless insanity.

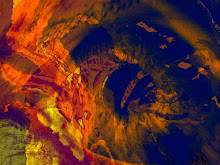

Cavernous expressions molded to fit the wretchedness typical of missed chances, but - bravo! - instantly canceled by honorable oblivion.

Understand what you can, dear.

Don't worry, it will be fine.

Love, Laolao

I wish I could tell you I was a happy child. I wish I could describe some fun events without suspicion having to invade the entire domain of my experiences.

Since she was a fashion designer, my mother was entitled to carry around the largest, sharpest scissors you can imagine. They were made of long, heavy blades. Their black handles so large, my hands could almost go through the holes.

She did try a couple of times to stab my father with them. I would be in bed downstairs, listening to my mother’s shouts, the accusations: A mistress here, a venereal disease there, money running out, spent on seduction masquerades. Never heard my father reply. He wept, feeling sorry for himself, working at staying out of reach of the scissors.

I disliked my mother’s outbursts, but I thought she was basically in her right to be pissed. I wished though she would have dropped the scissors. And perhaps my father, on his side, could have helped appease the scene by uttering something like “stop” or "sorry."

The scissors terrified me. They were my mother’s weapon of predilection whenever she ran out of insults. She actually didn’t know that many. Her vocabulary was modest. A thing rather than a flux. So the scissors often came in handy.

Conveniently, I can’t remember how our fight had started: I see my mother’s strong hands tightly squeezing mine around the handles of the scissors. I’m trying to free my fingers without making the scissors jerk. You see, my mother is pulling the scissors towards her stomach. She has the blades against her own body. She yells that I should kill her. As I pull in the opposite direction with all my might, I’m crying ‘Please, stop. Stop this.’

A proof by the way that I was much more articulate than my father.

A million thoughts go through a kid’s mind at such a moment. I can’t free my hands. She’s trying to puncture herself using me as an assassin. And I am so tired, baby, I am hoping that these melodramatic clashes can end right now. What if, for a fraction of a second, I stop pulling the scissors away from her? What if I simply relax my muscles?

Yes, the plan did germinate in my mind. And it’s not love or caring that prevented me from letting my mother fall into her own trap. No. It was a selfish move. I wasn’t sure at which age people could go to jail. At 10, I felt I was already a grown-up person. Who would have believed that my hands on the scissors had been forced?

So I pulled and pulled the scissors away from my mother, saving myself, not her.

My mother would always remind the world that she didn’t have a mother, therefore no role-model for her. She claimed to have done her best under the circumstances. I sort of believe her.

I taught myself to be a mother watching her, and I raised my children equipped with that oblique hint. In turn, they are now educating you, my grand-children, also readied by that history. There’s little I can do to change that, except through theoretical attitudes, unmasking the underground constructions that marked our family’s sub-culture, the dominance-submission rites we savagely danced to.

My memories, as you may have noticed, always seem to rise from such manipulative, reified debris.

They’re totally indoctrinated by a sense of ethics born from ancient reaction patterns. Redefined by a world essentially made of testimonials sentenced to destruction.

Sacred dreams of fairness, justice, equality vacillating between denied potentialities and self-proclaimed repression.

There’s no beam of truth highlighting my childhood souvenirs, no exoskeleton to protect them. Instead, it’s a sort of dissipated, undisciplined holographic light blurring all the way to non-existence formless fears, beyond rescue, sometimes diluting them in a vein of raw senseless insanity.

Cavernous expressions molded to fit the wretchedness typical of missed chances, but - bravo! - instantly canceled by honorable oblivion.

Understand what you can, dear.

Don't worry, it will be fine.

Love, Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment