I was reading this morning about tanks. It’s September first and in 1939, on this day, the Germans invaded Poland: Blitzkrieg, or a warfare strategy based on speed and mobility. The merger of three 20th century technologies: tanks, airplanes and the radio, with tanks being the key asset. That, and of course the element of surprise: A full armored attack without having declared war.

I have never known war. I’m part of the lucky few throughout history who were not subjected to the atrocities humans inflict upon each other.

Nevertheless, the first texts I memorized in primary school were Napoleon’s speeches to his troops. These motivational tirades fascinated me. I would stand on a chair to address my infantrymen and cavaliers, my voice resounding with assurance. I also had a clear preference for war movies over everything else shown on TV. I watched them all, a world of men, fearless, ready to give their life for a cause, advancing through chaos, impervious to the whistling of bullets, the crashing of bombs, immune to the sight of blood and dismembered bodies. Commanding officers shouting orders obedient soldiers followed to the letter, throwing themselves into battle at the precise moment they were told to.

I used to wake up very early as a kid, at around 4:30 or 5 in the morning, much before the sun. I loved our house then, quiet, a feeling of emptiness, of immobility that made me like it. I never turned on the lights, keeping the darkness as it was. I would slightly open the drapes in the living room and stare at our street.

There was a story that would constantly pop in my mind. Our street was elbow-shaped, our house the fourth one, right in the curve. The first three houses were close to one another. Then there was a small field bordered by our house. Our street led to a road mostly used by farmers. Lost cows, in those early years, would sometimes cross it and end up on our lawn.

Looking at our street, I would imagine a fire engulfing the first house, strong winds pushing the flames eastward, quickly consuming the second house, the third one soon ready to burn, the field separating our house from the blaze giving me just enough time to be the hero of the day and save my family.

But at this point, my story always went wrong. I would imagine myself climbing the steps to the top floor to wake my parents up. Desperately shaking them, telling them to get up, to run, a deadly fire was coming. Quick, hardly time to escape. I would cry, stomp, swear to them I was saying the truth. Plead. Make a racket. But to no avail.

No one would believe me. My parents wouldn’t budge. They stayed in bed telling me to go away, to leave them alone. In my story, I would run back and forth, from the living room window to their bedroom, screaming the fire was fast approaching.

And then, the big, awful moment comes where I have to decide. The hideous, outrageous, decision. As our house is starting to burn, smoke hurting the eyes, I ask myself what to do. Do I stay? Do I run away and leave them behind? If I wait too long, I’ll die. If I leave, they die. Am I a hero?

Because smoke moves up, the bedrooms upstairs are already filled with thick, unbreathable air, do I tell myself. I am too small to drag everyone’s body downstairs. There’s only my youngest sister that I can save. And I end my story this way. Running out the front door with the baby in my arms, in my pajamas, barefoot in the snow.

I truly felt bad about this story. I tried many times to change it. It was my story after all. I should have been able to modify its content. To get the characters to behave differently. To listen to me. But the story would unfold by itself, take over, always caught in the same modus operandi.

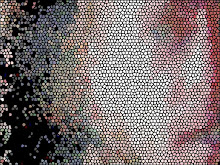

The only person I could save with the heroic efforts displayed in my fantasy was the one who could not exercise any free will. A baby, unable to make a decision, who didn’t know yet the words for refusal. Who had no ability to reject me.

This meant I was powerless over the world. To be right or wrong had no importance, for even when I was right, I had no influence. My actions had no impact. Nobody trusted me. My story showed people would choose to die instead of believing in me.

One of my teachers who had known the war in Europe had told us how she had lost her mother. They were fleeing their town, a long procession of people carrying a few belongings along a dirt road. Airplanes came down, a piece of shrapnel hitting her mother at the waist. My teacher, who was then a little girl, had to keep on walking, letting go of her mother’s hand, leaving her body behind.

Every time I went over her story in my mind, the dirt road took invariably the shape of ours, the planes dropping their bombs exactly when the little girl and her mother entered the curve where our house was located.

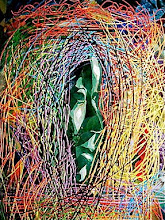

As you see, I had dreams, but I had them fully awake. I have never remembered a single dream made while asleep. Not once. I only have nightmares my eyes opened.

There was another story that used to monopolize my mind in the early hours of the day. I kept it for last because it was the most frequent one. Leaving the strongest impression because of its repetitive nature.

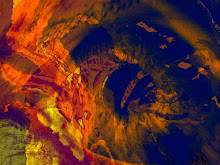

It had either tanks or a train in it. It’s like a scene from a silent movie. My vision is similar to that of a large screen in a theater. From the left side of the image, a long line of tanks appears. At other times, these look more like massive black wagons. At first, I feel relieved, they are moving away from me, going where the cows come from. But then, that damned curve on our street appears and the tanks turn, heading in my direction. I cannot move. I still have time to get out of their way, but my body won’t listen. It’s not responding. It stays there, heavy, paralyzed. Not by fear. I’m lucid. I know what to do. I can still save myself, just a few steps and I’ll be fine, uncrushed. I see the tanks getting closer. I can make it. If I could just throw myself out of their path, roll over. Not much, just enough. But nothing happens. I have no control over my limbs. I seem to be made of rocks, an amazing weight I can’t lift. I focus, a desperate effort at concentration, as the tanks keep getting closer. No sound. No noise. I can’t hear the engines. There’s only the sight of these huge machines bigger and bigger, an entire panzer division on the move, swift, speedy, agile, while I’m there, incapable of helping myself. My own body refusing to understand, to listen. Disregarding my orders. Ignoring me.

The variation with the train is not much different. I realize that the tracks have the same elbow shape as our street, leading the train straight through where I’m helplessly standing, inept, no power over my movements, totally enraged at my supreme incompetence. Defenseless. Worthless. The most impotent person one can imagine.

That was me. Daydreaming, my face peeking through the living-room curtains, observing the empty street as if it was a long virgin sheet of paper offering itself to fiction. Hours before it was time to get dressed and head for school. Having already lost everything to a full caravan of panzers roaming through a Quebec suburb.

War movies, indeed, fed my imagination. They taught me, among other things, how babies were made: This soldier at the front finally gets a letter from his wife announcing she’s pregnant. Since the young man has been fighting for a while, I gathered he had sent one of his spermatozoids in an envelope back home.

From then on, the postman, going from house to house everyday, had a new role. And I was careful never to touch the mail he would put in our box.

When I explained at school the efficient way society (via the Post Office) and nature were enmeshed to produce babies, I found it of course completely normal that no one expressed much faith in my theory.

(...) Soldats, lorsque tout ce qui est nécessaire pour assurer le bonheur et la prospérité de notre patrie sera accomplie, je vous renverrai en France ; là, vous serez l’objet de ma plus tendre sollicitude. Mon peuple vous reverra avec des transports de joie, et il vous suffira de dire : j’étais à la bataille d’Austerlitz pour que l’on réponde : voilà un brave.

Laolao

I have never known war. I’m part of the lucky few throughout history who were not subjected to the atrocities humans inflict upon each other.

Nevertheless, the first texts I memorized in primary school were Napoleon’s speeches to his troops. These motivational tirades fascinated me. I would stand on a chair to address my infantrymen and cavaliers, my voice resounding with assurance. I also had a clear preference for war movies over everything else shown on TV. I watched them all, a world of men, fearless, ready to give their life for a cause, advancing through chaos, impervious to the whistling of bullets, the crashing of bombs, immune to the sight of blood and dismembered bodies. Commanding officers shouting orders obedient soldiers followed to the letter, throwing themselves into battle at the precise moment they were told to.

I used to wake up very early as a kid, at around 4:30 or 5 in the morning, much before the sun. I loved our house then, quiet, a feeling of emptiness, of immobility that made me like it. I never turned on the lights, keeping the darkness as it was. I would slightly open the drapes in the living room and stare at our street.

There was a story that would constantly pop in my mind. Our street was elbow-shaped, our house the fourth one, right in the curve. The first three houses were close to one another. Then there was a small field bordered by our house. Our street led to a road mostly used by farmers. Lost cows, in those early years, would sometimes cross it and end up on our lawn.

Looking at our street, I would imagine a fire engulfing the first house, strong winds pushing the flames eastward, quickly consuming the second house, the third one soon ready to burn, the field separating our house from the blaze giving me just enough time to be the hero of the day and save my family.

But at this point, my story always went wrong. I would imagine myself climbing the steps to the top floor to wake my parents up. Desperately shaking them, telling them to get up, to run, a deadly fire was coming. Quick, hardly time to escape. I would cry, stomp, swear to them I was saying the truth. Plead. Make a racket. But to no avail.

No one would believe me. My parents wouldn’t budge. They stayed in bed telling me to go away, to leave them alone. In my story, I would run back and forth, from the living room window to their bedroom, screaming the fire was fast approaching.

And then, the big, awful moment comes where I have to decide. The hideous, outrageous, decision. As our house is starting to burn, smoke hurting the eyes, I ask myself what to do. Do I stay? Do I run away and leave them behind? If I wait too long, I’ll die. If I leave, they die. Am I a hero?

Because smoke moves up, the bedrooms upstairs are already filled with thick, unbreathable air, do I tell myself. I am too small to drag everyone’s body downstairs. There’s only my youngest sister that I can save. And I end my story this way. Running out the front door with the baby in my arms, in my pajamas, barefoot in the snow.

I truly felt bad about this story. I tried many times to change it. It was my story after all. I should have been able to modify its content. To get the characters to behave differently. To listen to me. But the story would unfold by itself, take over, always caught in the same modus operandi.

The only person I could save with the heroic efforts displayed in my fantasy was the one who could not exercise any free will. A baby, unable to make a decision, who didn’t know yet the words for refusal. Who had no ability to reject me.

This meant I was powerless over the world. To be right or wrong had no importance, for even when I was right, I had no influence. My actions had no impact. Nobody trusted me. My story showed people would choose to die instead of believing in me.

One of my teachers who had known the war in Europe had told us how she had lost her mother. They were fleeing their town, a long procession of people carrying a few belongings along a dirt road. Airplanes came down, a piece of shrapnel hitting her mother at the waist. My teacher, who was then a little girl, had to keep on walking, letting go of her mother’s hand, leaving her body behind.

Every time I went over her story in my mind, the dirt road took invariably the shape of ours, the planes dropping their bombs exactly when the little girl and her mother entered the curve where our house was located.

As you see, I had dreams, but I had them fully awake. I have never remembered a single dream made while asleep. Not once. I only have nightmares my eyes opened.

There was another story that used to monopolize my mind in the early hours of the day. I kept it for last because it was the most frequent one. Leaving the strongest impression because of its repetitive nature.

It had either tanks or a train in it. It’s like a scene from a silent movie. My vision is similar to that of a large screen in a theater. From the left side of the image, a long line of tanks appears. At other times, these look more like massive black wagons. At first, I feel relieved, they are moving away from me, going where the cows come from. But then, that damned curve on our street appears and the tanks turn, heading in my direction. I cannot move. I still have time to get out of their way, but my body won’t listen. It’s not responding. It stays there, heavy, paralyzed. Not by fear. I’m lucid. I know what to do. I can still save myself, just a few steps and I’ll be fine, uncrushed. I see the tanks getting closer. I can make it. If I could just throw myself out of their path, roll over. Not much, just enough. But nothing happens. I have no control over my limbs. I seem to be made of rocks, an amazing weight I can’t lift. I focus, a desperate effort at concentration, as the tanks keep getting closer. No sound. No noise. I can’t hear the engines. There’s only the sight of these huge machines bigger and bigger, an entire panzer division on the move, swift, speedy, agile, while I’m there, incapable of helping myself. My own body refusing to understand, to listen. Disregarding my orders. Ignoring me.

The variation with the train is not much different. I realize that the tracks have the same elbow shape as our street, leading the train straight through where I’m helplessly standing, inept, no power over my movements, totally enraged at my supreme incompetence. Defenseless. Worthless. The most impotent person one can imagine.

That was me. Daydreaming, my face peeking through the living-room curtains, observing the empty street as if it was a long virgin sheet of paper offering itself to fiction. Hours before it was time to get dressed and head for school. Having already lost everything to a full caravan of panzers roaming through a Quebec suburb.

War movies, indeed, fed my imagination. They taught me, among other things, how babies were made: This soldier at the front finally gets a letter from his wife announcing she’s pregnant. Since the young man has been fighting for a while, I gathered he had sent one of his spermatozoids in an envelope back home.

From then on, the postman, going from house to house everyday, had a new role. And I was careful never to touch the mail he would put in our box.

When I explained at school the efficient way society (via the Post Office) and nature were enmeshed to produce babies, I found it of course completely normal that no one expressed much faith in my theory.

(...) Soldats, lorsque tout ce qui est nécessaire pour assurer le bonheur et la prospérité de notre patrie sera accomplie, je vous renverrai en France ; là, vous serez l’objet de ma plus tendre sollicitude. Mon peuple vous reverra avec des transports de joie, et il vous suffira de dire : j’étais à la bataille d’Austerlitz pour que l’on réponde : voilà un brave.

Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment