I bought you marbles. I will fly soon, in 10 days, and we’ll be able to play together. I’ll show you. We’ll draw a circle on the ground (I’ll bring the chalk or we can use a stick) and each our turn we’ll throw our glass balls to knock those we’ve already rolled inside the circle.

It’s not that fun really. After a few minutes, you’ll get bored.

I suspect you’ll quickly take the marbles and pretend they’re something else. You’ll put them in some plastic pots and pans to cook for a teddy bear. Or in your pocket as if they were coins to use when shopping at an imaginary grocery store. Maybe you’ll bury them in the yard to see if plants can grow out of them. You might even let them sink in the fish tank and watch them add forms and colors to the coral bed.

You’ve always diverted, rerouted your toys.

I like that about you.

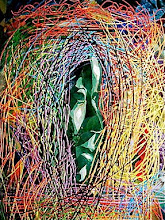

I do not recall games in my childhood. Life was way too serious, and I couldn’t distract my focus, even for an instant, from the need to hold together all the parts I was made of, worried they would drift away if I was to let go.

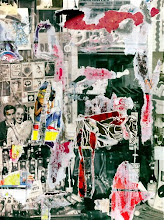

But I did transfer my preoccupation, diligently surveying the outcomes of disembodiment. I cut a lot. To start with, the Sears catalogue. As soon as I had sufficient hand coordination to manage scissors, I felt compelled to try out new faces on the bodies printed on the pages, test the effects of different pairs of legs on the models. I would cut out the clothes and superpose them on the pictures of people there to show accessories, dresses, washing machines or cosmetics. Mix and match. I did that for hours. Reorganizing the looks of that multitude, hundreds of individuals all static in their poses, wanting them able to become other beings, stranger than they already were as strangers to me.

Day after day, I went on cutting and reassembling. You can view, it’s alright dear, I don't mind, such an obsessive activity as a kind of exorcism. Hourly rituals to keep harm at bay. Repetitions of the same to eventually make a big difference.

A mild form of self-inflicted autism, perhaps.

I knew very early on something was wrong. Because I was the only one capable of hearing my voice when I said so, I’m not well. My father-the-eminent-psychologist would not be acknowledging any time soon that his offspring was somewhat impaired. My mother-the-elegant-fashion-designer on her side would be doing the exact opposite, an exaggerated use of my peculiarities to explain and justify her own misery in the midst of suburban solitude.

Very little, in fact, was to be said about me as a young child. So I kept on cutting as an odd approach to society and its members. Narrowing my interests on new arrangements for Sears, the microcosm of the universe I knew I had to familiarize myself with, fragments isolated and handled one at a time so to, one day, be qualified to intermingle with the general population.

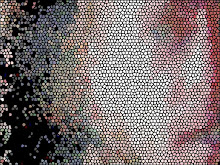

It was all about a recirculation of components. Tautologies to slowly form the habit of existing. Taming ideas by displacing them. Again and again and again. Making tiny portions, easier to embrace. Separating fractions, little lumps of two-dimensional people less aloof than those tall ones walking around with their unsettling noises and personal dramas.

As I was cutting and pasting, I medicated myself by not truly responding to my own name, convinced deep down I must have had other names that had been broken, splintered, in very ancient times impossible to recollect, scraps of names like the pieces of papers scattered around me on the floor, countless segments and their fathomless combinations. Cut, cut, cut, I would go. Slashing my way through childhood. Codifying small amounts, unfit to take it all in one shot, in one panoramic view. Cataloguing the catalogue. Tabulating humanity’s visual data, clouding the boundaries between organic and inorganic.

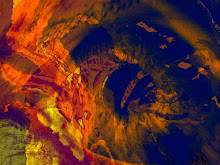

It was not therefore a game that I played, carefully ripping pages apart, not something to pass the time, or to entertain myself or others. When I was busy cutting and pasting, there were no others. Only the mechanical gestures required to hermetically shut down emotions, raising high up the skills to recognize and systemize the elements embroiled in life’s pandemonium, countering entropy, studying disarray to sort it all out, the facets, the details, every item urgently calling to be delineated and re-denominated. A big job. A mandate, duty to myself through restriction of behavior to make sure terra firma would stay intact under me despite new constructions and the elaboration of countless trial and non-permanent displays.

Not a hobby. Not a distraction. I had no sense of amusement back then.

I sternly zoomed in all my subject matters, a degree of concentration eclipsing everything else. An absolute generosity of time and energy, all devoted to the grouping and the new alignments of specks and shreds, their significance reconstituted along experimental grids. Searching for a benign way to be. An unfailing surface for things to be switched around and reconvened.

Your Laolao comes from far away, my darlings. Lots had to be undone, chiseled, truncated, before relationships became possible under the new management of shapes and measurements. Before I could grow, learn. Before I could be a person, creating other persons.

Like Lucky, this character in Waiting for Godot, I too have traveled a long time dragging a burdensome suitcase never thinking of simply leaving it behind. Though instead of rocks, mine’s filled with paper cut-outs. It’s a definite improvement, weight-wise.

So, for the game, please understand. I’ve checked the rules in Wikipedia. It will be my first time. I just look forward to being silly and not losing the marbles.

Ciao, Laolao

It’s not that fun really. After a few minutes, you’ll get bored.

I suspect you’ll quickly take the marbles and pretend they’re something else. You’ll put them in some plastic pots and pans to cook for a teddy bear. Or in your pocket as if they were coins to use when shopping at an imaginary grocery store. Maybe you’ll bury them in the yard to see if plants can grow out of them. You might even let them sink in the fish tank and watch them add forms and colors to the coral bed.

You’ve always diverted, rerouted your toys.

I like that about you.

I do not recall games in my childhood. Life was way too serious, and I couldn’t distract my focus, even for an instant, from the need to hold together all the parts I was made of, worried they would drift away if I was to let go.

But I did transfer my preoccupation, diligently surveying the outcomes of disembodiment. I cut a lot. To start with, the Sears catalogue. As soon as I had sufficient hand coordination to manage scissors, I felt compelled to try out new faces on the bodies printed on the pages, test the effects of different pairs of legs on the models. I would cut out the clothes and superpose them on the pictures of people there to show accessories, dresses, washing machines or cosmetics. Mix and match. I did that for hours. Reorganizing the looks of that multitude, hundreds of individuals all static in their poses, wanting them able to become other beings, stranger than they already were as strangers to me.

Day after day, I went on cutting and reassembling. You can view, it’s alright dear, I don't mind, such an obsessive activity as a kind of exorcism. Hourly rituals to keep harm at bay. Repetitions of the same to eventually make a big difference.

A mild form of self-inflicted autism, perhaps.

I knew very early on something was wrong. Because I was the only one capable of hearing my voice when I said so, I’m not well. My father-the-eminent-psychologist would not be acknowledging any time soon that his offspring was somewhat impaired. My mother-the-elegant-fashion-designer on her side would be doing the exact opposite, an exaggerated use of my peculiarities to explain and justify her own misery in the midst of suburban solitude.

Very little, in fact, was to be said about me as a young child. So I kept on cutting as an odd approach to society and its members. Narrowing my interests on new arrangements for Sears, the microcosm of the universe I knew I had to familiarize myself with, fragments isolated and handled one at a time so to, one day, be qualified to intermingle with the general population.

It was all about a recirculation of components. Tautologies to slowly form the habit of existing. Taming ideas by displacing them. Again and again and again. Making tiny portions, easier to embrace. Separating fractions, little lumps of two-dimensional people less aloof than those tall ones walking around with their unsettling noises and personal dramas.

As I was cutting and pasting, I medicated myself by not truly responding to my own name, convinced deep down I must have had other names that had been broken, splintered, in very ancient times impossible to recollect, scraps of names like the pieces of papers scattered around me on the floor, countless segments and their fathomless combinations. Cut, cut, cut, I would go. Slashing my way through childhood. Codifying small amounts, unfit to take it all in one shot, in one panoramic view. Cataloguing the catalogue. Tabulating humanity’s visual data, clouding the boundaries between organic and inorganic.

It was not therefore a game that I played, carefully ripping pages apart, not something to pass the time, or to entertain myself or others. When I was busy cutting and pasting, there were no others. Only the mechanical gestures required to hermetically shut down emotions, raising high up the skills to recognize and systemize the elements embroiled in life’s pandemonium, countering entropy, studying disarray to sort it all out, the facets, the details, every item urgently calling to be delineated and re-denominated. A big job. A mandate, duty to myself through restriction of behavior to make sure terra firma would stay intact under me despite new constructions and the elaboration of countless trial and non-permanent displays.

Not a hobby. Not a distraction. I had no sense of amusement back then.

I sternly zoomed in all my subject matters, a degree of concentration eclipsing everything else. An absolute generosity of time and energy, all devoted to the grouping and the new alignments of specks and shreds, their significance reconstituted along experimental grids. Searching for a benign way to be. An unfailing surface for things to be switched around and reconvened.

Your Laolao comes from far away, my darlings. Lots had to be undone, chiseled, truncated, before relationships became possible under the new management of shapes and measurements. Before I could grow, learn. Before I could be a person, creating other persons.

Like Lucky, this character in Waiting for Godot, I too have traveled a long time dragging a burdensome suitcase never thinking of simply leaving it behind. Though instead of rocks, mine’s filled with paper cut-outs. It’s a definite improvement, weight-wise.

So, for the game, please understand. I’ve checked the rules in Wikipedia. It will be my first time. I just look forward to being silly and not losing the marbles.

Ciao, Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment