I’ll go by dates, ok? I need them to position myself in relation to you.

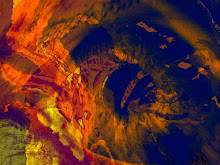

Today, 63 years ago, some eight years before my birth, Americans detonated their first atomic bomb. The ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed a few weeks later.

You will certainly, as you grow older, become familiar with the pictures of “House No. 1.” These black-and-white pictures are quite famous. The house was destroyed in about two seconds as part of Operation Upshot-Knothole, a test conducted in Nevada the year of my birth.

I was almost two years old when, for the first time, two nuclear devices were triggered on the same day, also in Nevada.

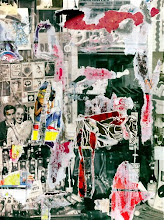

This is the context I grew up in, all the way to the Cuban missile crisis. By then, I was nine. A politicized nine, dutifully trained at the duck-and-cover-under-your-desk tactic to survive nuclear attacks.

I don’t know about the others, the kids in my class, how they coped with the mood of the time, but I can tell you I didn’t fare that well.

I felt a responsibility. A fault that was mine. Certainly, as I look back, a disproportionate sense of self-importance for thinking my own doings were somehow involved. I did ask my parents much later what they had thought the day the first bomb fell on Japan. The day they had read about it in the news. My parents looked at me, puzzled, and didn’t say a thing as if the question was irrelevant.

Today, my parents are both gone. And I don’t have that answer.

In my hometown, the Cold War did go sometimes below zero.

Can anyone remember that poster showing the Earth against a blue sky, the planet threatened by a gigantic sickle suspended over its North Pole?

Nuns had explained that each time we sinned, the communists pushed the sickle down and, one day, if we kept on misbehaving, it would cut the Earth in two.

First thing to do, count the sins witnessed during the day. This implies that sins have already been defined and duly listed on the basis of predetermined criteria laid out by experts (such as nuns).

Two, multiply the number of sins in one’s immediate environment taking into account the world’s population so to have an approximate idea of the pressure put on that sickle.

Three, and that’s the tricky part, one needs to know the speed at which that sickle is coming down, and the distance it must cover before it reaches us – for this, I had to develop hypotheses and conservative estimates, a difficult task for someone my age.

Fourth, check the sky. Always, always check the sky. Never get your eyes off the sky. Calculations may be incorrect, but that sickle is getting closer, that’s sure, doesn’t matter what my numbers are. Eventually, it will appear as a shiny golden line over our head.

So, check the sky. Do not sleep. During the day in school, sit by the window. Check the sky, always, always. Must warn the others. Maybe we have a chance if we do not end up exactly where the Earth is split.

This is, my dear grand-children, how for the first time your Laolao fell.

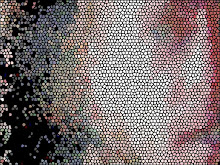

My body stiff like a stone. Not fainting, no. I could hear, see, think. I was paralyzed, couldn’t move, not even my eyes.

I fell backward like a hard plank of wood, hit the floor, and just stayed there, immobile, unable to pick myself up.

I could hear the commotion around me. I could see faces bent over me. All my muscles as rigid as steel. No feelings. No fear. No questions. Just a slight surprise at finding myself so comfortable, so free within myself. I heard people shout I was dead. I tried to say I wasn’t, but realized I had no sound in me, no movements on my lips.

That was all. A vague impression of happiness, of lightness. The rest, completely deactivated.

It happened at school, grade one.

The nuns weren’t that stupid, they knew abnormal behavior when they saw it. Hence, they called my parents.

My father, the psychologist, said it was nothing to worry about. As a consequence, I spent a large part of my childhood falling into this weird kind of physical coma. Repeated-impromptu-annihilations of the body, each episode lasting for a few minutes. No interventions necessary. No help needed. No care given. Not a word at home about my peculiarities. I was stuck with these unusual collapses as if they were an integral part of my personality.

Wasn’t scared, but of course the other kids were. Didn’t make friends.

These bouts of catalepsy happened during quite a few years. I can only say that I owe their disappearance to only one person (don’t laugh, please): President Kennedy.

You see, it’s on TV. My mother thinks today could very well be the end of the universe The neighbors are already hidden in their basement. Kennedy is speaking to the world. October 1962. I don't think am afraid. I'm interested. I’m looking at this man on the TV screen. He sounds aware, concerned. He seems to have some sort of knowledge. He’s strong, I can tell by his words, the way he articulates them, clearly. I like his voice. He speaks in English. He lives far away. Maybe over there, men are something else. I wish I could go where he is. Things have specific names in his mouth. He has all sorts of words to describe his intentions. I’m sure he has thoughts because he speaks about them. I may not understand all of what he says, but he’s convinced me he’s saying something. I sense a purpose when he talks. It even seems important at times.

I’ll stay in front of the TV, I’ll watch him. I’ll wait for him. I might even believe.

The world did not end that day, nor the next day. My mother was wrong; the president, right. As for my father, I don’t know where he was, probably being a psychologist somewhere.

That, my sweet ones, it’s called closure. That’s what Kennedy did, he closed an era.

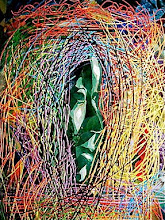

From the poster with the sick sickle to the messy missile crisis, I had busied myself expressing with my body's rigidity, or seizures, the idea of death. Made it into a joke, a caricature. Played with it. Imitated it. Tested it. Mocked it. Confirmed it. I gave it a shape. And a weight. A profile. I had proved it. Made it happen. Again and again for the skeptics.

Now, no longer an off-and-on 'cataleptic,' (for lack of a better term), I started to feel things. Anger. Of course, had absolutely to read Marx.

At 13, I tried to apply for membership with the Canadian Communist Party. At the time it made sense; it took into account stories and history. The guys over there told me to grow up. So I went back to reading. What else could I do?

Ciao, Laolao

Today, 63 years ago, some eight years before my birth, Americans detonated their first atomic bomb. The ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki followed a few weeks later.

You will certainly, as you grow older, become familiar with the pictures of “House No. 1.” These black-and-white pictures are quite famous. The house was destroyed in about two seconds as part of Operation Upshot-Knothole, a test conducted in Nevada the year of my birth.

I was almost two years old when, for the first time, two nuclear devices were triggered on the same day, also in Nevada.

This is the context I grew up in, all the way to the Cuban missile crisis. By then, I was nine. A politicized nine, dutifully trained at the duck-and-cover-under-your-desk tactic to survive nuclear attacks.

I don’t know about the others, the kids in my class, how they coped with the mood of the time, but I can tell you I didn’t fare that well.

I felt a responsibility. A fault that was mine. Certainly, as I look back, a disproportionate sense of self-importance for thinking my own doings were somehow involved. I did ask my parents much later what they had thought the day the first bomb fell on Japan. The day they had read about it in the news. My parents looked at me, puzzled, and didn’t say a thing as if the question was irrelevant.

Today, my parents are both gone. And I don’t have that answer.

In my hometown, the Cold War did go sometimes below zero.

Can anyone remember that poster showing the Earth against a blue sky, the planet threatened by a gigantic sickle suspended over its North Pole?

Nuns had explained that each time we sinned, the communists pushed the sickle down and, one day, if we kept on misbehaving, it would cut the Earth in two.

I was perhaps five or six. And not so smart for my age. My high sense of logic has always been detrimental to my mental health.

I had of course devised a procedure:

I had of course devised a procedure:

First thing to do, count the sins witnessed during the day. This implies that sins have already been defined and duly listed on the basis of predetermined criteria laid out by experts (such as nuns).

Two, multiply the number of sins in one’s immediate environment taking into account the world’s population so to have an approximate idea of the pressure put on that sickle.

Three, and that’s the tricky part, one needs to know the speed at which that sickle is coming down, and the distance it must cover before it reaches us – for this, I had to develop hypotheses and conservative estimates, a difficult task for someone my age.

Fourth, check the sky. Always, always check the sky. Never get your eyes off the sky. Calculations may be incorrect, but that sickle is getting closer, that’s sure, doesn’t matter what my numbers are. Eventually, it will appear as a shiny golden line over our head.

So, check the sky. Do not sleep. During the day in school, sit by the window. Check the sky, always, always. Must warn the others. Maybe we have a chance if we do not end up exactly where the Earth is split.

This is, my dear grand-children, how for the first time your Laolao fell.

My body stiff like a stone. Not fainting, no. I could hear, see, think. I was paralyzed, couldn’t move, not even my eyes.

I fell backward like a hard plank of wood, hit the floor, and just stayed there, immobile, unable to pick myself up.

I could hear the commotion around me. I could see faces bent over me. All my muscles as rigid as steel. No feelings. No fear. No questions. Just a slight surprise at finding myself so comfortable, so free within myself. I heard people shout I was dead. I tried to say I wasn’t, but realized I had no sound in me, no movements on my lips.

That was all. A vague impression of happiness, of lightness. The rest, completely deactivated.

It happened at school, grade one.

The nuns weren’t that stupid, they knew abnormal behavior when they saw it. Hence, they called my parents.

My father, the psychologist, said it was nothing to worry about. As a consequence, I spent a large part of my childhood falling into this weird kind of physical coma. Repeated-impromptu-annihilations of the body, each episode lasting for a few minutes. No interventions necessary. No help needed. No care given. Not a word at home about my peculiarities. I was stuck with these unusual collapses as if they were an integral part of my personality.

Wasn’t scared, but of course the other kids were. Didn’t make friends.

These bouts of catalepsy happened during quite a few years. I can only say that I owe their disappearance to only one person (don’t laugh, please): President Kennedy.

You see, it’s on TV. My mother thinks today could very well be the end of the universe The neighbors are already hidden in their basement. Kennedy is speaking to the world. October 1962. I don't think am afraid. I'm interested. I’m looking at this man on the TV screen. He sounds aware, concerned. He seems to have some sort of knowledge. He’s strong, I can tell by his words, the way he articulates them, clearly. I like his voice. He speaks in English. He lives far away. Maybe over there, men are something else. I wish I could go where he is. Things have specific names in his mouth. He has all sorts of words to describe his intentions. I’m sure he has thoughts because he speaks about them. I may not understand all of what he says, but he’s convinced me he’s saying something. I sense a purpose when he talks. It even seems important at times.

I’ll stay in front of the TV, I’ll watch him. I’ll wait for him. I might even believe.

The world did not end that day, nor the next day. My mother was wrong; the president, right. As for my father, I don’t know where he was, probably being a psychologist somewhere.

That, my sweet ones, it’s called closure. That’s what Kennedy did, he closed an era.

From the poster with the sick sickle to the messy missile crisis, I had busied myself expressing with my body's rigidity, or seizures, the idea of death. Made it into a joke, a caricature. Played with it. Imitated it. Tested it. Mocked it. Confirmed it. I gave it a shape. And a weight. A profile. I had proved it. Made it happen. Again and again for the skeptics.

Now, no longer an off-and-on 'cataleptic,' (for lack of a better term), I started to feel things. Anger. Of course, had absolutely to read Marx.

At 13, I tried to apply for membership with the Canadian Communist Party. At the time it made sense; it took into account stories and history. The guys over there told me to grow up. So I went back to reading. What else could I do?

Ciao, Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment