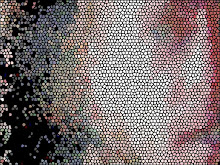

You represent, not one, but all of my grand-children. Those who are at this date, and those who will be. All the children my children have had and will have.

On the lookout for moments that could have the traits of an origin, I’ve come up with this:

You have a mother/father, one of them has me, your laolao, as a mother (it's either my son or my daughter).

I had a mother myself (her), but she never knew her own mother.

Hence (we’re lucky to be working with binaries), we need to switch, for the sake of the story, to my father’s mother (my grand-mother/your great-great-grand-mother).

There’s a tacit assumption, of course, that she had, too, a mother, but we’ll consider this ancestor blameless as she is deeply buried, out of reach, under the theater of operations where I’ve set up, for the purpose of continuity, all my supply lines. In other words, I’m sorry to say we don’t know who this great-great-great-grand-mother was.

Each generation we’re dealing with since her has had its own chain of command, usually asymmetrical. Each generation has also worked hard at elevating fortifications, as well as various veto mechanisms that made sure martial rule never fell into enemy hands.

On security grounds, everybody, in those days, was rationed, tricked, and mobilized with the strategic goal of arriving at a perfectly round ethnocentric world. This was considered parental self-defense.

Rival factions weren’t tolerated: The male side of our society eventually ending up deported or subject to war-time forms of internment. Civil liberties were curtailed, kept at bay by indiscriminate space blockades bearing the flags of neurotic policies. Yes, we drafted men, acquiring their territories, and called them the defeated side.

In other words, we were raised, the girls, as an omnipotent warrior class for mutually assured destruction.

I was no exception, trained to perpetuate humanitarian crises, a specialist in anti-personal landmines and unilateral belligerency. We, the girls, were simultaneously, for as long as I can remember, both the aggressors and a significant part of the collateral damage, unable to stand anywhere else than in the cross-fire. And I’ll tell you, it’s an impediment.

In the semantic biographies recounting our female struggles, from mothers to daughters, one would find the equivalent of kilotons of thermonuclear-based tactics used to fight in the name of extinction. We waged scientific wars, a major feature in our history, but constantly contradicted ourselves by engaging in semi-diurnal rituals to demonize our own governing bodies.

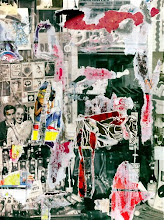

We were in fact, as a collective of women, made of tightly united opposing forces, pitched against one another, finding common denominators, the crazy glue, in discordance itself.

We had a few slogans: The efficiency of our nervous system must be both misleading and ruthless. At sunset, our daughters are nothing more than a bunch of apprentice barbarians; their resounding cheers should not detract us from abandoning them outside the fences. When streets are deserted, never think of forgiveness. Obey instantly your interrogators. Be frightened to death at the most trivial or polite comment.

At the confluence of extensive conflict theories, one can see how, generations ago, we had already established supremacy in all wars of words, each of us, matriarch, demanding total surrender. Commanders in chief ordering hostilities and retaliations, making sure no war crime tribunals would ever stand in the open.

But all of this fails to explain the very nature of warfare itself as we kept reconducting it.

We resort again and again to instinctual arguments, invoking principles of universal occurrences found in the human character to validate, in undeniable efforts of denial, diplomatic justifications and their subsequent eternal disputes.

We have no idea, really, why we are so ready to sacrifice ourselves, why we are willing – in a rough maternal role – to nurture unrest as the bargaining chip to avoid overwhelming failure at our various educational and colonial tasks.

In this particular family lineage into which I found myself, we have never once calculated the costs of our inter-tribal fighting.

Our only incentive has always been to constantly extract concessions, to optimize reciprocal stalemates for further decisive accusations, while we also engaged in the negative view of peace as a threat to our feeling of identity.

Self-sufficient, we generated in full confidence all the internal heat we needed using flourishing bouts of blackmail and revenge: the energy behind labyrinths of production lines churning out traumas and new recruits.

Our smiles were infuriating. They led to abundant, personalized, self-replicating acts of sabotage advertised as best deals, sure as we were that endemic psychological violence prospers best with skillfully armored intentions.

These traditions were never inscribed in an interest for wars of independence. On the contrary, we have always been listed as an outgrowth of misplaced power and imperial missions aimed at destabilizing all relations and moral questions.

With fanfare, we held on to complicated and cumulative competition as a cunning solution.

Perhaps my mother was a war bride. I was a war baby. And before us, someone, another woman, wearing war paint collapsed in a war cry. It could have very well started this way, we’ll never know.

We only know that my ancestors and I have always been totally involved in the organization of catastrophes. We are war profiteers, constantly in a countdown position to launch wishful delusions about our dominions.

And as I desperately rebelled one day against all of this, in turn I became the same, and burned down the entire city. Rough estimates of the casualties have yet to reach my headquarters.

I thus coexist alongside highly controversial ideas about the ‘motherland,’ and have not yet succeeded in convincing populations that it was worthwhile to disengage myself, pushing the emergency button right in the midst of zero gravity.

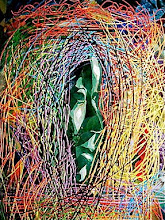

When I did that, sirens immediately erupted in my head and I spiraled helplessly as if in a vortex. All my circuitry was impaired. I became impossible to maneuver. Indivisible conical thoughts obstructed my brain modules with the most distressing effects: perfectly engineered toxic emissions.

The only salvation came from giving up all types of manual controls. In the onslaught, I had outnumbered myself, but I was fortunate: I had unwillingly created a new kind of artificial gravity: idiosyncratic interspaces where matter in motion could stay solid, in a palpable form.

By then, I had left America, then Europe to live in Asia.

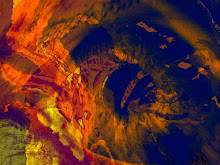

In this new surrounding, I felt invigorated, redefined, at the dawn of possible happiness, finally deprived of internalized social roots, uninfluenced by secondary factors, resurrected, undifferentiated, never pushed by the force of objections, paying off all my debts, frightfully glad to see myself enter a complete state of renunciation.

I hid my face in my hands to better look at the sky where the future eventually would be flying. And I saw myself in it, an airborne living organism surviving the brazier.

I stared, astounded, at the logo of China. I couldn’t understand a single word of what was said around me.

The master in me and the slave in me had to stop communicating. I finally had arrived beyond dialogue. No more signified. No more signifier. No signifying distractions. No available spoken or written primordial alibi for my actions.

Only total aberrations altering all conceivable parameters.

I had escaped the ‘repetition of the present,’ to quote Artaud. The obscure fabric of Mandarin had put me, momentarily, at the source of a truce, the temporary absence of knowledge about the incredible furor within myself.

You need to know all of this, my little one(s). The sutures and the ruptures. Time and time again in the past, they chaperoned me until, each time, I dropped to my knees and, holding back the entire breadth of my breath, begged uselessly for respite.

You’ll need to be careful; stay away from the overzealous minds of our genealogy.

Remember, beloved: As if by magic, to avoid wreckage, all you must do is to laugh out loud. Keep customs under bubble wrap. Make no photocopies of them. And do not address the grievances of your elders.

Once it’s Zulu time, no mob involvement.

Laolao

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

photo+album).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment